On 9 September 2025, Israel is understood to have launched an audacious attack against the HAMAS political leadership in Qatar, reportedly through the use of air-launched ballistic missiles launched from Israeli fighter aircraft over the Red Sea. While there is nothing new about this Israeli capability set, and although China is no stranger to air-launched ballistic missile technology, the Israeli attack on Qatar nevertheless highlights a type of difficult-to-counter attack that China is increasingly well-positioned to undertake across the Indo-Pacific. This post expands on themes and analyses that have appeared in several of my previous writings that are available on this website:

Israel’s Air-Launched Ballistic Missiles

Before discussing the Israeli attack and whether China can emulate it, it is first important to underscore that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is not the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and will likely never be able to replicate the IDF in general and the Israeli Air Force’s (IAF) approach to air combat operations more specifically even if Israel provided China the exact aircraft and exact munitions used to attack Qatar. The IDF in general and the IAF in particular have mastered a highly aggressive—almost mindlessly aggressive—and high-tempo approach to warfare that often catches both friend and foe off guard. I like to draw analogies to the similarly highly aggressive nature of German ground forces at the tactical and operational levels in both world wars, as well as Napoleonic France at the tactical and operational levels. As I explained in the first of the above—now somewhat outdated—posts on China’s air-launched ballistic missiles, which contains a fairly detailed survey of air-launched ballistic missile technology including the distinct Israeli experience, China and Israel appear to have not only developed very different air-launched ballistic missiles but also pursued air-launched ballistic missile technology for very different reasons.

By circa 2010, the IAF was encountering a situation in which Iran and Syria, among other countries in the region, were set to receive long-range surface-to-air missile systems. While the IAF planned to eventually receive a large number of American F-35 low-observable fighters, it recognized that the bulk of its fleet would be composed of non-low-observable F-15 and F-16 fighter aircraft for the foreseeable future. For the likes of the F-15 and F-16 to remain competitive against long-range surface-to-air missile systems such as the Russian (late model) S-300 and S-400, and to allow the IAF to retain its longstanding primary role of serving as a battering ram to rapidly knock out adversary air defences and combat aircraft—preferably on the ground, Israel turned to air-launched ballistic missiles. With this new—for fighter aircraft, as opposed to bomber aircraft—type of air-launched strike munition, the IAF could undertake its longstanding role in Israel’s preferred extremely high intensity but—crucially—very short conflicts. With air-launched ballistic missiles capable of rapidly neutralizing the core components of the likes of an S-300 or S-400 long-range surface-to-air missile system, the IAF could attain not only so-called air superiority but also free reign to attack hundreds, if not thousands, of discrete aim points per day (over short distances—sortie rates and the maximum number of aim points that can be serviced per day drop precipitiously as flight radiuses increase). It goes without saying that this reflects a highly aggressive and high-tempo approach to air combat operations that, in turn, places extremely high demands on air and ground crew alike, command and control capabilities, readiness, target intelligence, and, of course, the availability of suitably equipped aircraft and suitable munitions.

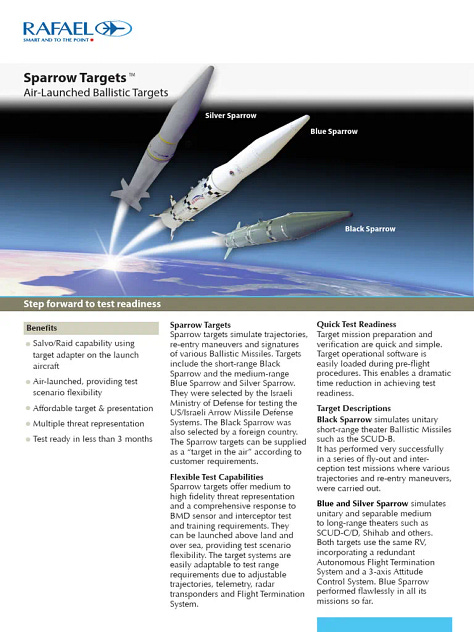

To neutralize adversary air defences and, in so doing, enable the IAF to operate in full force, Israeli industry is understood to have pursued two distinct types of what amounts to an air-launched ballistic missile. While the IAF could have pursued a purpose-developed clean-sheet design, Israeli industry appears to have first adapted existing ground-launched large-caliber guided artillery rockets for aerial launch. The best known of these designs, the Elbit Rampage, was operational by 2019, if not earlier, and was used to undertake short-time-to-target standoff strikes against targets in Syria in which the IAF’s non-low-observable F-15 and F-16 fighter aircraft did not need to penetrate Syrian airspace. It is worth noting that the Rampage has a reported maximum range of 250 kilometers—which allows the launch aircraft to remain beyond the reach of the vast majority of air defence systems and even beyond the coverage of most radars—while being compact and light enough to be carried by the IAF’s F-16I strike fighter aircraft. At around the same time, Israeli industry is understood to have adapted a series of ballistic target missiles, which were used to support the development and test the effectiveness of Israel’s Arrow-2 and Arrow-3 ballistic missile defence systems, into much longer-range air-launched ballistic missiles. Some of these ballistic target missiles, such as the Blue Sparrow, can be carried and launched by the IAF’s F-15I strike fighters. At some point, Israeli industry also developed an air-launched version of the ordinarily surface-launched ballistic missile. Each of the IAF’s F-16I strike fighters can carry two air-launched LORA ballistic missiles to attack targets over a distance of at least 400 kilometers.

By developing and deploying such munitions, the IAF developed a multi-faceted capacity to, in effect, severely damage, if not destroy, non-hardened structures and objects such as early warning radars and the core components of air defence systems over distances of up to 1400 or more kilometers within mere minutes of launch. It bears emphasis that we are dealing with the capacity to attack such distant targets within mere minutes of launch in the hands of an air force that can, in effect, order its suitably loaded fighter aircraft to take-off and, after reaching launch altitude over Israeli airspace within minutes, subsequently attack targets located essentially anywhere within a distance of 1400 or so kilometers within mere minutes. Consider, for example, the possibility of an air-launched ballistic missile-equipped Chinese fighter aircraft taking off from an airbase on Hainan Island and, 10-15 minutes later, the impact of the warheads somewhere on the Philippine island of Luzon.

In addition to several previews in the context of the Syrian Civil War, Israel offered the world a glimpse of its air-launched ballistic missile capability in 2024, when Israel appears to have employed some of its longest-range air-launched ballistic missiles to attack targets in Iran. Israel’s apparent large-scale use of air-launched ballistic missiles in the opening phase of the June 2025 Iran-Israel War, therefore, came as little surprise to any observer who had been following developments in the IAF’s strike capabilities over the past fifteen or so years. True to form, the IAF used its air-launched ballistic missiles to rapidly neutralize Iranian air defences—Israel also employed special forces and intelligence agents inside Iran to attack Iranian air defences and other targets with drones of various types as well as guided surface-to-surface/anti-tank missiles. As with essentially every other country with a significant enough military to warrant mention, Iran was heavily reliant on a fairly small number of stationary long-range early warning radars—long-range search/acquisition radars, many of which were placed on hilltops or mountaintops as a result of Iran’s highly mountainous topography. With Iran having negligible ballistic missile defence capabilities, the IAF’s air-launched ballistic missiles were effectively employed in the primary role of battering rams that rapidly knocked out adversary air defences and, in so doing, enabled the IAF’s large fleet of fighter aircraft to attain not only air superiority over Iran but also have free reign to attack dozens, if not hundreds, of discrete aim points in Iran per day. It bears emphasis that the IAF’s logistics were likely to have been strained close to breaking point during the extremely high-intensity but very brief twelve-day war—most of Iran is over 1000 kilometers from Israel, while Tehran is some 1450 kilometres away.

When Israel attacked HAMAS’ political leadership in Qatar on 9 September 2025, Israel’s air-launched ballistic missile capability was a known quantity. The target was, however, unexpected and, more importantly for the purposes of this post, Israel is reported to have launched multiple air-launched ballistic missiles of an unknown type(s) over the Red Sea. If Israel had launched air-launched ballistic missiles against Qatar from Syria or Iraqi airspace, the operation would have been no less audacious but would have been less interesting for the present purposes. The closest part of Israel to the Doha metropolitan area is around the southernmost Israeli city of Eilat, which lies along the Gulf of Aqaba. Eilat is some 1700 kilometers from Doha. To significantly reduce the distance that had to be covered, the involved Israeli fighter aircraft would have had to fly over the Gulf of Aqaba and over the Red Sea proper. From a distance of around 1700 kilometers from a launch point at the Strait of Tiran, the flight distance to the Doha metropolitan area drops to approximately 1350 kilometers in the vicinity of Yanbu, Saudi Arabia. No point of the Red Sea is closer than 1250 kilometers from Doha, so there would have been little incentive for the Israeli fighter aircraft carrying the air-launched ballistic missiles to have flown much further south than Yanbu.

The above discussion of where the Israeli fighter aircraft launched the air-launched ballistic missiles is relevant for the present purposes concerning China, not because it deals with distances, but because it highlights the ability of air-launched ballistic missiles to approach a target from a very different launch geometry—from a different compass bearing. To appreciate the importance of this attribute of air-launched ballistic missiles, which can by definition be launched from locations that result in attacks on targets that approach from bearings that a ground-launched ballistic missile cannot match, we must recognize that all individual radar antennas have a field of view of no more than 120° (in some cases just ~60° or ~90°). The specific types of early warning/acquisition and engagement/fire control radars that can detect and track ballistic missiles must, in effect, stare at a given sector—stare in the direction of a specific bearing—while limited to a field of view of no more than 120°. While the details are not public knowledge, the IAF is very likely to have launched ballistic missiles from the Red Sea not only with the aim of bringing the Doha metropolitan area within range—supposing that Israel does not possess air-launched ballistic missiles with a maximum range of 1700 or more kilometers—but to attack Doha from a direction in which the air-launched ballistic missiles could not be detected by ground-based radar—we are dealing with a time-to-target/flight time of around 10-15 minutes—or intercepted.

China’s Air-Launched Ballistic Missiles

China is no stranger to air-launched ballistic missile technology and is known to operate at least two air-launched ballistic missiles as well as at least one air-launched boost-glide vehicle (BGV—also known as a hypersonic glide vehicle, or HGV). The JL-1 air-launched ballistic missile, which was formally unveiled at the 3 September 2025 military parade in Beijing, and the air-launched BGV are solely carried and launched by the PLA Air Force’s (PLAAF) reportedly nuclear-capable H-6N bombers. The H-6N is a specially configured—a single oversized air-launched ballistic missile can be attached to a semi-recessed weapons station underneath the fuselage—and aerial refuelling capable derivative of the PLAAF’s H-6K, which is the PLAAF’s most widely deployed bomber aircraft. While a non-nuclear version of the JL-1 and the air-launched BGV may exist, the JL-1 is understood to be a nuclear-armed air-launched ballistic missile.

The PLAAF’s H-6K bomber fleet, as well as its much smaller fleet of closely related H-6J bomber aircraft, which were transferred to the PLAAF from the PLA Navy Air Force in 2023, can be equipped with a much smaller and shorter-range air-launched ballistic missile that was also formally unveiled at the recent military parade with the designation YJ-21. While the YJ-21 designation denotes an air-launched anti-ship ballistic missile, the YJ-21 may be capable of attacking terrestrial targets, and a dedicated land-attack version of the YJ-21 may also exist.

The PLAAF’s bomber force may be able to use at least one other air-launched ballistic missile of unknown design and role that appears to be designated KF-22. Uncertainties concerning the apparent KF-22 notwithstanding, none of the PLA’s publicly known air-launched ballistic missiles can be carried by PLAAF fighter aircraft such as the J-10C and J-16 in the manner that most, if not all, of Israel’s air-launched ballistic missiles are carried by its F-15I and F-16I fighter aircraft—the IAF does not possess any bomber aircraft. Chinese industry is, however, known to have developed at least one much smaller and lighter air-launched ballistic missile that is so far associated with—of all possible options—the CH-9, which is a turboprop-powered fixed-wing ISR drone that is broadly analogous to the American MQ-9 Reaper.

While there is so far no public indication that the PLAAF has adopted this much smaller and lighter air-launched ballistic missile design of uncertain designation, such a missile would allow the PLAAF’s large fleet of twin-engine J-16 fighters, and perhaps its large fleet of more range-restricted single-engine J-10C fighters, to employ long-range and high-speed—short-time-to-target—standoff munitions in much the same manner as the IAF. The PLAAF may also emulate Israel’s use of the Rampage as a shorter-range air-launched ballistic missile analogue. The Rampage is a derivative of the 306 mm diameter EXTRA guided artillery. Functional analogues to the Israeli EXTRA exist in the PLA arsenal, and China’s military industry has developed a remarkably diverse array of medium- and large-caliber artillery rockets, including guided artillery rockets, many of which are only used by export customers. Chinese analogues to the Israeli Rampage, as well as the Israeli air-launched LORA, are all well within the realm of possibility.

It goes without saying that the PLA does not strictly need air-launched ballistic missiles to increase the reach of its strike capabilities in the manner of Israel. The PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) is well-positioned to serve as the PLA’s battering ram in the opening phase of a conflict that involves the likes of Taiwan, Japan, and, above all, the United States. The PLARF arsenal is, however, limited in terms of numbers, there are untold thousands of discrete aim points that the PLA will likely have to attack in a major war, and most of missiles in the PLARF arsenal are essentially overkill for many of the distant and, in some cases, time-sensitive targets that the PLA is likely to attack in a major war, such as, for example, an early warning radar site in the Philippines. While the likes of the YJ-21 air-launched (anti-ship) ballistic missile extend the reach of the PLAAF bomber fleet, the PLAAF will require air-launched ballistic missiles in the vein of those operated by the IAF to dramatically increase the reach and enhance the strike capabilities of its 1500 or so non-low-observable fighter aircraft and similar (excluding the J-7 variants that remain in service, as well as the low-observable J-20 and J-35/J-35A).

Consider the following scenario. A notional 1000-kilometer range air-launched ballistic missile carried by PLAAF fighter aircraft and launched over the South China Sea can be used to attack targets on the island of Taiwan from a south-southwest direction that Taiwan’s ballistic missile defences do not otherwise need to be oriented toward. A notional 400-kilometer range design in the vein of the Israeli Rampage can allow some of the PLAAF’s oldest and least competitive non-bomber combat aircraft, such as the JH-7A, J-11B, and perhaps the J-10A, to undertake long-range and short-time-to-target attacks on Taiwan from safe launch positions located well within Chinese airspace. A notional 1000-kilometer range air-launched ballistic missile carried by PLAAF fighter aircraft can also allow the PLAAF fighter brigades subordinate to Southern Theater Command (STC) to independently undertake long-range strikes against high-value and/or time-sensitive targets in the Philippines and perhaps elsewhere in Southeast Asia in a manner that allows STC to not maximally draw upon the PLAAF bomber fleet and the PLARF more generally, which are likely to focus on targeting the American island of Guam and possibly Japan in a major conflict. A smaller, lighter, and shorter-range design in the vein of the Israeli Rampage can also allow PLAAF fighter brigades subordinate to STC to independently undertake standoff attacks against targets in the Philippines that are located in, for example, the Manila metropolitan area, a sector that is likely to be reinforced by the United States military in time of war.

While this post focuses on combat operations along China’s eastern oceanic frontier, it is worth noting that air-launched ballistic missiles can also be productively used against India in a conflict along the Himalayas, which is a potential conflict area that the bulk of the PLARF is not oriented toward in peacetime, as well as one in which the PLARF units redeploying westward encounter considerable logistical constraints.

The PLA in general and the PLAAF in particular stand to benefit immensely from the development and deployment of air-launched ballistic missiles along the lines of the systems in use by the IAF. It bears emphasis that most of the surface area in which the potential targets of Chinese strike munitions are located across the Indo-Pacific is not protected by any ground-based air defence systems at all, and very little of it is protected by ground-based ballistic missile defences. The Philippines, for example, which appears set to play an increasingly important role as a forward-basing node for the American military in a major war with China, presently possesses negligible air defence capabilities and no ballistic missile defences whatsoever. What little air defence capabilities the Philippines possesses are woefully inadequate to protect even the Manila metropolitan area, let alone the rest of the sprawling archipelagic country. Even Japan, a country that possesses an impressive array of air defence and ballistic missile capabilities, is likely to struggle against a PLAAF that aggressively employs air-launched ballistic missiles in the manner that the IAF did against Iran in June 2025 and against Qatar more recently.

It bears emphasis that while such attacks can and likely will be undertaken by the PLARF using ground-launched missiles of different types, a major conflict to determine the fate of Taiwan is likely to become a protracted war, one in which the PLAAF will likely have to carry much of the burden of attacking untold thousands of discrete aim points across the Indo-Pacific. Air-launched ballistic missiles compatible with the PLAAF’s 1500 or so non-bomber non-low-observable combat aircraft will allow it to undertake such missions. The absence of such a long-range standoff strike capability, which can only be partially substituted for through the deployment of air-launched ballistic missiles and the use of aerial refuelling aircraft to extend the range of fighter aircraft more generally, will likely result in a situation in which the PLAAF is unable to carry this immense burden in a protracted conflict scenario.

As I explained near the start of this post, the PLA is not the IDF—even the American military does not operate like the IDF—and the PLAAF is unlikely to be able to replicate the IAF’s extremely high-intensity approach to air combat operations even if Israel were to transfer to China the exact aircraft and exact munitions used to attack Qatar. As things stand, the PLA is a very different organization, one that does not appear to exhibit the flexibility, initiative, and even the aggression of the IDF in general and the IAF in particular. That said, the PLAAF is well-positioned to employ air-launched ballistic missiles from not only its bomber aircraft but also its fighter aircraft. In so doing, the PLAAF will acquire its own battering ram with the aim of creating openings for the rest of the PLAAF and the rest of the PLA more generally to take advantage of.