China's Latest Submarine Rescue Ship Transits The Tsushima Strait Into the Sea of Japan, Draws Attention To The PLAN's Deep Sea Capabilities

🇨🇳

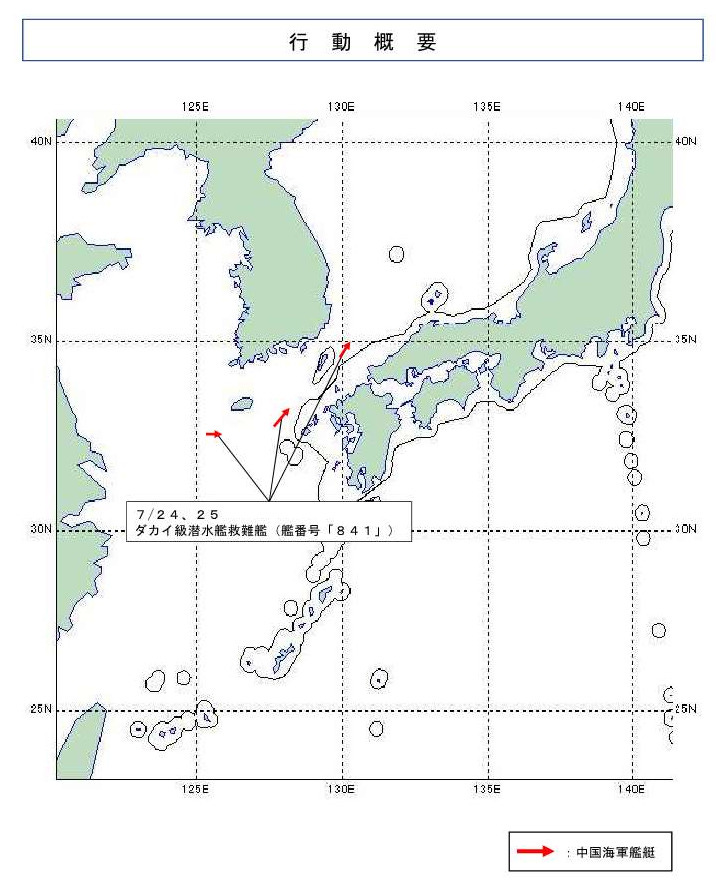

On 25 July 2025, Japan’s Joint Staff Office issued a press release announcing the transit of a Chinese submarine rescue ship into the Sea of Japan by way of the Tsushima Strait. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) submarine rescue ship in question is hull #841, which is designated the Dakai-class by the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence. The Chinese submarine rescue ship #841 was commissioned in 2024 and is the second hull of a three-strong new class of submarine rescue ships that will complement the PLAN’s three smaller Type 926-class submarine rescue ships, which were commissioned in the early 2010s.

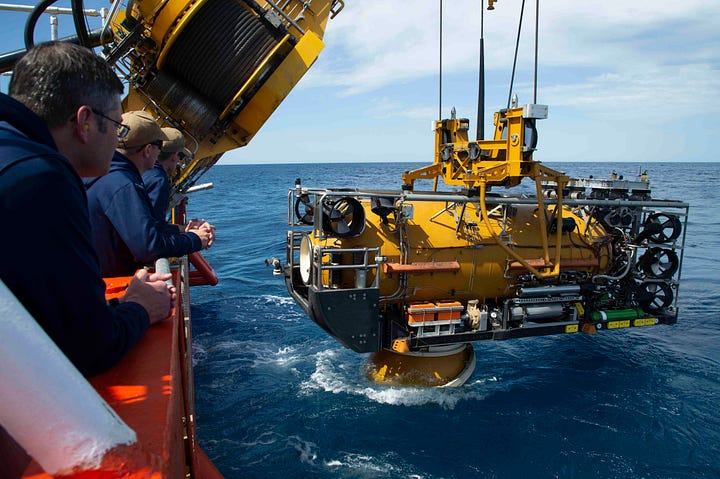

While submarine rescue ships are inherently multi-purpose naval auxiliaries, these primarily exist to transport and serve as a mothership supporting the operations of a deep sea rescue vehicle (DSRV). DSRVs are highly specialized unarmed crewed submersibles designed to rescue personnel from disabled submarines. Submarine rescues are best avoided and are, for most practical intents and purposes, essentially irrelevant in cases in which a disabled submarine was operating in very deep water that exceeded the crush depth of the submarine hull—and the crush depth of the DSRV. For navies that primarily operate submarines in the littorals, however, which is primarily the case for navies operating large numbers of diesel-electric submarines and a grouping which notably includes the PLAN, submarine rescue ships are not only a necessity but have a realistic prospect of rescuing the crew of a disabled submarine, at least in peacetime.

The PLAN submarine rescue ship #841 was built at the Guangzhou Shipyard International (GSI) shipyard located on Longxue Island in Guangzhou. A vessel of this class was notably pictured at this shipyard with a mockup of a Z-8 helicopter on its large helicopter landing deck, which is located in front of the bridge to allow for the external carriage of a DSRV, various pieces of often oversized supporting equipment, and a large crane.

The existence of a flight deck compatible with the Z-8 helicopter—and the related Z-18 helicopter—is notable given that the Z-8 and Z-18 are primarily land-based helicopters in PLAN service unless these are embarked on a PLAN aircraft carrier, large amphibious warship, or replenishment ship. PLAN warships go to sea with hangars and landing decks that are only capable of supporting much smaller and lighter Z-20, Ka-28, and Z-9 series helicopters. Submarine rescue ships require a flight deck because medical personnel and other supplies have to be transported onboard the submarine rescue ship, and ambulatory rescued submarine crewmembers and those requiring urgent medical care not available on the submarine rescue ship will have to be transported to another ship or to a shore-based medical facility.

While China has an independent submarine rescue capability, it has relatively limited experience in this area and deep water submerged operations more generally in comparison to the United States and Russia, which are the longstanding leaders in this highly specialized area of activity and technology. It is possible that the submarine rescue ship #841 is in the Sea of Japan with the aim of participating in a submarine rescue training event with the Russian Navy, which will likely amount to an invaluable experience for the involved PLAN personnel. It is important to note that the Russian Navy is currently holding its annual summer training events and that there is also a PLAN surface group currently in the Sea of Japan. The surface group in question is composed of the Type 052D-class destroyers Urumqi (#118) and Shaoxing (#134), as well as the Type 903-class replenishment ship Qiandaohu (#886). The Type 052D-class destroyers are both equipped with a Combined Diesel Or Gas (CODOG) propulsion system and are capable of sustaining a much higher speed than the diesel-powered replenishment ship Qiandaohu (#886). While it is unclear why the submarine rescue ship #841 did not make the transit through the Tsushima Strait as part of this PLAN surface group, there is presently no indication that this is an unplanned urgent deployment intended to undertake a real-life submarine rescue attempt on a disabled PLAN submarine.

The PLAN’s large fleet of auxiliaries tends not to receive adequate attention, and the PLAN’s submarine rescue ships are no exception. It bears emphasis that submarine rescue capabilities are closely related to underwater salvage capabilities, which can be used to recover submerged Chinese and foreign aircraft, missiles, and other types of military equipment. While the PLAN has vessels and personnel dedicated to the undertaking of salvage missions, deep sea salvage is a highly specialized undertaking that is intimately tied to the capacity to put in place and retrieve unattended underwater sensors, tap and/or severe submarine communication capabilities, as well as damage or destroy underwater infrastructure more generally.

While China has a large fleet of state-owned oceanographic vessels and similar, not all of which are painted grey or operated by PLA personnel, there is no publicly known Chinese analogue to the Russian military’s Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research, the Russian abbreviation for which is transcribed as GUGI, or highly specialized ships such as the Russian Yantar, which serves as a mothership to multiple highly specialized deep sea submersibles that are designed to undertake underwater intelligence gathering and/or subotage missions. It is important to note that Russia’s GUGI also operates several very large and specially modified submarines, including nuclear-powered designs, to serve as underwater motherships for deep sea submersibles.

While China may or may not develop a highly specialized capability set analogous to that which exists in Russia’s GUGI, the PLAN nevertheless requires a large fleet of submarine rescue ships in order to expand the presence of the large PLAN submarine fleet within the so-called First Island Chain and Second Island Chain, let alone to support the operations of PLAN submarines in more distant waters. Although there are reports and documented cases of PLAN submarines operating in the Indian Ocean, these appear to be primarily associated with diesel-electric submarines, which constitute the bulk of the PLAN’s submarine fleet. Operating submarines in general and diesel-electric submarines in particular in distant waters comes with considerable risk for the PLAN, given that it may be unable to deploy a submarine rescue ship in time to rescue the crew of a disabled Chinese submarine that has bottomed on the sea floor without exceeding its crush depth. It is important to note that submarine rescue ships and suitable merchant ship substitutes, namely offshore support vessels, have hull forms and propulsion systems that offer a top speed of no more than 15-20 knots (~28-37 km/h).

While the PLAN has the option of forward-deploying one or more of its expanded fleet of submarine rescue ships in the Indian Ocean, the only plausible forward bases at the present time are in Pakistan or Djibouti, all of which are toward the extreme west of the Indian Ocean. Given this and other considerations, the PLAN may come to emulate the American approach to submarine rescue. While it operates the world’s largest fleet of nuclear-powered submarines and has multiple submarines deployed around the world on any given day, the U.S. Navy does not operate any dedicated submarine rescue ships. It instead relies on an air-transportable capability set called the Submarine Rescue Diving and Recompression System (SRDRS), which includes a remotely-operated (i.e., uncrewed) submersible called the Pressurized Rescue Module (PRM), which can rescue up to sixteen submarine crewmembers per trip.

As with the preceding and now retired DSRVs Mystic and Alavon, which were commissioned in the 1970s, the American PRM DSRV is loaded onto a plane, flown to an airport near the location of the disabled submarine, and then loaded onto a suitable vessel near said location. This allows the U.S. Navy to initiate a submarine rescue within several days of this capability set being activated, something that is simply not possible with ship-deployed DSRVs unless a submarine is disabled at a location within several days sailing time-distance of a DSRV-equipped mothership. The alternative is, of course, to deploy multiple DSRV-equipped motherships around the world, but that entails a very substantial resource allocation—DSRVs are highly specialized and very expensive custom-made systems—and the commitment of an impractically large number of personnel.

If the PLAN is serious about developing an expeditionary submarine capability that facilitates regular diesel-electric and/or nuclear-powered submarine operations beyond the so-called First Island Chain and the western-most parts of the so-called Second Island Chain, it will likely have to emulate the air-transportable DSRV approach, an option that is enabled by the availability of increasing numbers of Chinese-built Y-20A and Y-20B military transport aircraft, which are analogues to the American C-17. The alternative is, of course, to deploy multiple DSRV-equipped motherships in the areas that the PLAN intends to deploy submarines, but that entails a very substantial resource allocation—DSRVs are highly specialized and very expensive custom-made systems—and the commitment of an impractically large number of personnel.

Given the construction of multiple new submarine rescue ships—including the #841—around a decade after commissioning three Type 926-class submarine rescue ships, the PLAN appears unlikely to emulate the American approach for the foreseeable future. This has implications for the PLAN’s ability to deploy diesel-electric- and/or nuclear-powered submarines far from the Chinese coastline. That said, it is possible that the PLAN intends to employ its submarine rescue ships as multi-role deep sea motherships that can be used to deploy submersibles other than DSRVs for underwater intelligence and/or sabotage roles in the manner of Russia’s GUGI. The new submarine rescue #841 and its sister ships do not, however, share design similarities with the likes of the Russian Yantar, which has multiple features indicative of its optimization toward use as a multi-purpose mothership to different types of submersibles. As with so many areas of China’s military capabilities, the country’s submarine rescue capabilities remain a work in progress notwithstanding the construction and deployment of new systems.