Disclosures Concerning Operation Rough Rider Highlight The Limitations Of The U.S. Navy's Standoff Strike Capabilities

🇺🇸 🇾🇪

While the United States and Ansarallah in Yemen were engaged in regular combat operations between October 2023 and March 2025, it took Operation Rough Rider (March-May 2025), a sustained American air and missile strike campaign, to fully expose the limitations of the U.S. Navy’s air-launched standoff strike capabilities. Operation Rough Rider offered observers a window into both the strengths and limitations of the U.S. military in general and the U.S. Navy in particular against an unconventional adversary that lacked an air force and even a conventional air defence system but nevertheless benefited from an advantageous military-geographical context and deployed a fairly simple but nevertheless effective “guerrilla air defence” capability set.

Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. military has followed a “playbook” of sorts. The United States utilizes its unmatched logistical capabilities to forward-deploy its forces, including land-based fighter aircraft, to one or more locations close to the country it is set to commence operations against—or in, if the target is an armed non-state actor—and then initiates combat operations at a time and place of its choosing with a total overmatch in capabilities. Where geography permits, the United States has the option of sending one or more aircraft carriers to do much the same—deploy within several hundred kilometers from the intended target and undertake aerial bombing with carrier-borne fighter aircraft at will in a context in which essentially no adversary—with the singular and recent exception of China—can contest the might of the United States at sea in an all-out conflict.

In Operation Rough Rider, the United States was unable to follow this “playbook” against Ansarallah. No nearby country was willing to allow American combat aircraft to operate from their soil against Ansarallah because Ansarallah’s Iran-supplied land-attack strike capabilities and the fierce disposition of Ansarallah’s leadership—who have displayed a remarkably high risk appetite and pain threshold—make it a particularly unpleasant adversary to fight, not least when there are more high-value targets for Ansarallah to attack in other countries than said countries can attack in Ansarallah-controlled areas of Yemen without creating a humanitarian catastrophe. The ability of the United States to credibly extend air and ballistic missile defence coverage to one or more countries willing to host American combat aircraft appears to have meant little against the potent threats posed by Ansarallah’s Iran-supplied ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and propeller-driven strike drones, and the United States was, as such, forced to heavily rely on the U.S. Navy to launch air and missile strikes against Ansarallah.

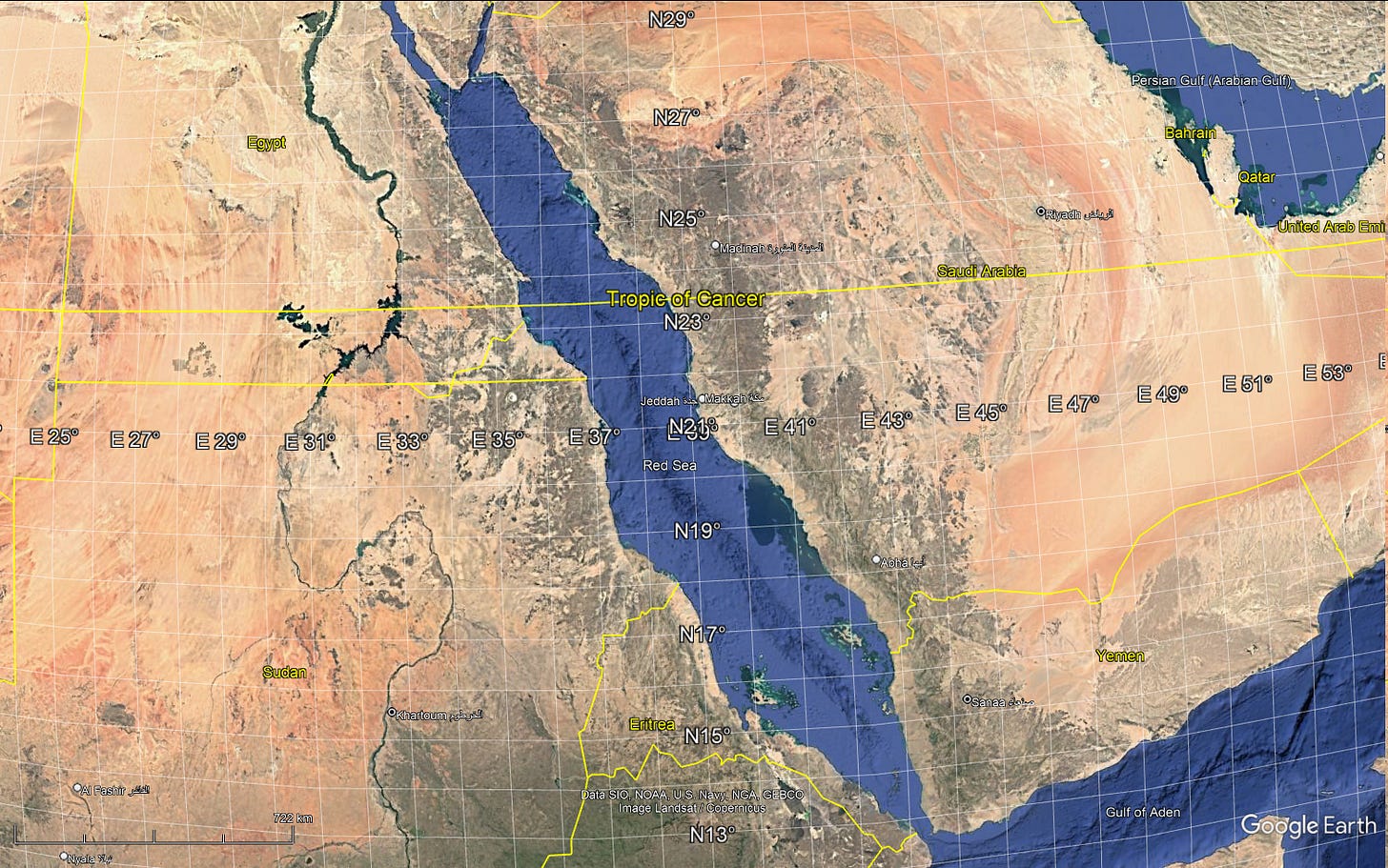

While Ansarllah has no open-water/blue-water naval capabilities to speak of, and certainly cannot hope to go head-to-head with the United States Navy with ships at sea, Ansarallah’s Iran-supplied maritime strike capabilities and Yemen’s mountainous geography put it in a very good position to incentivize U.S. Navy ships, including aircraft carriers, to remain several hundred kilometers from the Yemeni coastline. Since the start of the Ansarallah-U.S. conflict in October 2023, American aircraft carriers have typically maintained a distance of 500 or more kilometers from the Yemeni coastline. During Operation Rough Rider, the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman was typically operating north of the Tropic of Cancer, which is to say around 1000 kilometers from the Yemeni coastline.

The reasons for this are straightforward: while Ansarallah’s Iranian-supplied maritime strike capabilities are not omnipotent, the Red Sea is a narrow and, of course, essentially confined body of water. Being in a part of the world in which high-visibility atmospheric conditions are the norm, Ansarallah can readily turn to commercially available low-resolution satellite imagery—and a variety of other means—to discern the general area in which U.S. Navy warships and aircraft carriers are operating and thereafter send cruise missiles and/or strike drones, which are capable of searching for a suitable target, to that area. If potential targets are sufficiently proximate to northwestern Yemen and if Ansarallah has access to accurate target location data, it can also employ one of several Iranian-supplied anti-ship ballistic missiles. In this context, the U.S. Navy decided to be risk-averse and minimize its exposure to fire. In practice, this meant remaining very far from the Yemeni coastline even if this had the practical effect of diminishing the strike capabilities of carrier air wings independent of the potency of Ansarallah’s “guerrilla air defence capabilities.”

Given the finite number of Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles in existence and the limited number of RGM-109 Tomahawk-equipped vertical launch cells on U.S. Navy warships in the area, as well as the limited number of UGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missiles carried by U.S. Navy submarines in the area, United States Central Command (CENTCOM) was, in practice, forced to heavily rely on the strike capabilities of the U.S. Navy’s carrier air wings. At the start of Operation Rough Rider, the U.S. Navy presence in the region was centred on four squadrons of F/A-18E/F fighters on board the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman (Carrier Strike Group 8) in the Red Sea. In time, the United States sent the USS Carl Vinson (Carrier Strike Group 1) from the Western Pacific to the Arabian Sea to provide CENTCOM with two aircraft carriers for use against Ansarallah in Operation Rough Rider. Embarked on the USS Carl Vinson was one squadron of F-35C fighters and three squadrons of F/A-18E/F fighters.

As the days turned to weeks, a steady stream of images and videos released by the U.S. military, as well as a steady stream of images and videos captured of munitions debris by Yemenis, suggested that the U.S. Navy’s carrier air wings were heavily relying on not only a large albeit nevertheless finite stockpile of standoff air-to-ground munitions, but also a quite limited selection thereof. The U.S. Navy’s carrier-borne strike fighters appeared to be using plentiful and inexpensive unpowered JDAM-equipped non-glide optimized guided bombs when and where possible—presumably against targets close to northwestern Yemen’s non-mountainous coastline —and several longer-range standoff air-to-ground missiles—including the powered AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER and the unpowered AGM-154 JSOW—against more distant targets, presumably those in the mountainous Yemeni highlands, including the Sana’a metropolitan area. In addition, the U.S. Navy appeared to be employing powered AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missiles and the new and quite expensive unpowered GBU-53 guided glide bomb.

Being forced to employ carrier-borne fighter aircraft in a decidedly suboptimal manner as a result of the unfavourable military-geographical context vis-a-vis Ansarallah in the Red Sea—a decidedly suboptimal manner that had the practical effect of eroding the United States’ otherwise formidable capacity to damage and destroy hardened and/or deeply buried targets—the United States deployed a detachment of six B-2 “stealth” bombers to the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia. The B-2 bombers were presumably used to not only attack hardened and/or deeply buried targets against which the limited variety and supply of standoff munitions available to U.S. Navy carrier-borne aircraft may have been qualitatively inadequate, but also to attack a much larger number of discrete aim points than would be possible with carrier-borne fighter aircraft operating from a floating airbase that tended to remain some 1000 kilometers from the nearest part of the Yemen coastline.

The following two videos were shared by the CENTCOM X/Twitter account on 23 March 2025. Such videos and associated press releases offered observers a window into how CENTCOM was employing the U.S. Navy’s air-launched, ship/surface-launched, and submarine-launched strike capabilities against Ansarallah during Operation Rough Rider.

Did the United States Employ AGM-158C Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) Cruise Missiles Against Ansarallah?

Over the course of Operation Rough Rider and in its aftermath, observers received a steady stream of American media reports highlighting the high rate of munitions expenditure, including fairly scarce and quite expensive high-end strike munitions. This grouping of munitions reportedly included not only surface/subsurface-launched Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles but also AGM-158 JASSM family air-launched land-attack cruise missiles. For the present purposes, the AGM-158 JASSM family refers to both the original AGM-158A JASSM and the AGM-158B JASSM-ER air-launched land-attack cruise missiles (i.e., the extended-range version, which is, among other things, equipped with a turbofan engine instead of the original turbojet). Media reports offer no insight as to whether the U.S. military purposefully prioritized the employment of the older and shorter-range AGM-158A against Ansarallah or if it was forced to employ the newer and longer-range AGM-158B JASSM-ER for any number of potential reasons. While the AGM-158A and AGM-158B are currently the only versions of the JASSM family of land-attack cruise missiles deployed by the U.S. military, it is important to note that the U.S. military also operates the AGM-158C Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), which is the anti-ship missile derivative of the AGM-158B JASSM-ER.

In itself, reports of the employment of AGM-158 JASSM family land-attack cruise missiles against Ansarallah in Operation Rough Rider raised important questions. Although the U.S. Navy had declared an objective to integrate the AGM-158B JASSM-ER on its carrier-borne F/A-18E/F fighter aircraft in 2022, the language found in publicly available Fiscal Year 2025 budgetary documents—which were released in 2024—suggested that the integration of the AGM-158B JASSM-ER may not have been completed by the April 2025 start of Operation Rough Rider. While a possibility existed that the U.S. Navy was launching AGM-158 JASSM family cruise missiles from the F/A-18E/F fighters hosted by the USS Harry S. Truman (Carrier Strike Group 8) in the Red Sea—the USS Carl Vinson arrived in the region after the first reports emerged of the use of the AGM-158 JASSM family against Ansarallah—following an unannounced emergency or expedited integration effort, there was no information to confirm this.

While American officials have to date remained quiet as to which aircraft launched AGM-158 JASSM family land-attack cruise missiles against Ansarallah and where said aircraft operated from, recent images of U.S. Air Force F-15E strike fighters returning from a seemingly very eventful nine-month deployment in Jordan indicated that just eleven USAF F-15E fighters had collectively launched no fewer than forty-four AGM-158 JASSM family land-attack cruise missiles in that timeframe. All things considered, it is likely that some—perhaps all—of these AGM-158 JASSM family cruise missiles were employed against Ansarallah in Yemen as part of Operation Rough Rider as opposed to being employed against Iranian nuclear facilities in the single-day Operation Midnight Hammer on 22 June 2025, an operation in which the U.S. Air Force F-15E aircraft likely also participated in. I covered these newly released images of the USAF F-15E strike fighters and this dynamic in a recent post:

While the AGM-158 JASSM family, the F-15E, and the employment of AGM-158 JASSM land-attack cruise missiles against Ansarallah and/or Yemen cast a positive light on the standoff strike capabilities of the U.S. Air Force, it nevertheless bears emphasis that being forced to rely on land-based combat aircraft located over 1500 kilometers from northwestern Yemen to undertake such attacks reflects poorly on the preparation of the U.S. Navy’s carrier air wings to undertake standoff strikes against a distant target.

Did the United States Employ AGM-158C LRASM Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles Against Ansarall

While American media reports and now images of USAF F-15E aircraft with AGM-158 JASSM family-shaped markings strongly suggest the employment of said land-attack cruise missiles against Ansarallah as part of Operation Rough Rider, American budgetary documents also indicate the possible employment of AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missiles against Ansarallah in Yemen. The budget document indicates the reallocation of an additional US$90,000,000 toward AGM-158C LRASM production, which is the approximate cost of twenty-seven or so such missiles.

Before proceeding, it is important to note that this possible revelation comes from a Department of Defense reprogramming document, which is to say a document that concerns the reallocation of previously allocated funds to new purposes. Although the reallocation of funds toward additional AGM-158C LRASM procurement may be indicative of the employment of this very munition against Ansarallah, there is a distinct possibility that additional AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missiles are being procured to backfill the confirmed expenditure of AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER air-launched cruise missiles by the U.S. Navy. The AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER is a versatile cruise missile design that can be employed against both surface ships and terrestrial targets. Unlike the AGM-158C LRASM, the AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER is not currently in production and cannot, as such, be subject to a like-for-like replacement to make up for the depletion of U.S. Navy stocks—the U.S. Air Force does not operate the AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER. It is also important to note that publicly available budget documents indicate that the AGM-158C LRASM will not be deployed with a purpose-developed land-attack capability for the foreseeable future. The specifics are not, however, public knowledge, and it is possible that the AGM-158C LRASM is deployed in a configuration with at least a residual land-attack capability for use on an emergency basis.

Supposing that the AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missile was used against Ansarallah as a part of Operation Rough Rider, the candidate aircraft types to have employed this air-launched anti-ship cruise missile are U.S. Air Force B-1B bombers, U.S. Navy F/A-18E/F fighters, and U.S. Navy F-35C fighters. There are no reports of U.S. Air Force B-1B bombers participating in Operation Rough Rider, and of the two aircraft carriers that participated in the operation, only the USS Carl Vinson, which was operating in the Arabian Sea, had embarked F-35C fighters. Through the process of elimination and assuming that the budget documents do indeed indicate the employment of AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missiles in Operation Rough Rider, these anti-ship cruise missiles were presumably employed by F/A-18E/F fighters operating from either of the two involved aircraft carriers. Given that Ansarallah does not operate large surface ships for which such a high-end anti-ship cruise missile would be optimized, any AGM-158C LRASM employed in Operation Rough Rider were likely used to attack terrestrial targets.

To speculate, are there plausible scenarios in which the U.S. Navy would allocate an AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missile—a still new, rather scarce, and quite expensive munition—against a terrestrial target in Yemen? In brief, yes. Suppose, for example, that the U.S. military received intelligence about a high-value target, such as the location of a meeting of Ansarallah leaders and/or technical experts, in the central areas of Ansarallah-controlled territory in the Yemeni highlands. Suppose, moreover, that the meeting was being held in a structure that amounted to a hardened and/or deeply buried target. Relatedly, the hypothetical meeting may have taken place in an area assessed to be home to a high concentration of Ansarallah’s “guerrilla air defence capabilities.”

Given the military-geographical context of Operation Rough Rider in the Red Sea, which affected the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman, the likely expenditure of ready-for-launch Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles loaded in the vertical launch cells of nearby American surface ships and submarines, and the fact that commercially-available satellite imagery suggests that the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson may have exclusively remained east of Soqotra in the Arabian Sea, it does not strain credulity to imagine a situation in which the high-priority target warranted an immediate air or missile strike.

The problem that the U.S. military was encountering was the fact that American carrier-based fighter aircraft were operating at a radius of around 1000 kilometers. With both F-35C and F/A-18E/F fighters being restricted to subsonic speeds over such immense distances, there would be a fairly negligible difference in the time-to-target of the carrier-based fighter aircraft, on the one hand, and an air-launched cruise missile launched by said carrier-based fighter aircraft, on the other hand. The potential problem the U.S. Navy may have faced in such a situation is that neither AGM-158A JASSM nor AGM-158B JASSM-ER air-launched land-attack cruise missiles may have been integrated onto either the F/A-18E/F or the F-35C. As a result, the only available long-range—1000+ km maximum range—standoff munition available to the carrier air wings may have been the AGM-158C LRASM, the anti-ship version derivative of the AGM-158 JASSM land-attack cruise missile family. It is worth pointing out that the USS Carl Vinson was not originally deployed to the CENTCOM area of responsibility; it was, rather, deployed to the Western Pacific. Between the two American aircraft carriers, the USS Carl Vinson is the natural candidate for having left port loaded with some number of relatively scarce AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missiles for what was supposed to be a deployment in the Western Pacific.

The Bigger Picture: Placing The Spotlight On The U.S. Navy’s Limited Standoff Strike Capabilities

Perhaps the AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missile was not employed in Operation Rough Rider against Ansarallah in Yemen. Perhaps there was no operational need for U.S. Navy carrier-based fighters to launch any such long-range cruise missile against a terrestrial target. Perhaps the budgetary reprogramming notification simply reflects the backfilling of out-of-production AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER stocks with in-production AGM-158C LRASM missiles. Even if the AGM-158C was not used against Ansarallah in Yemen for any number of reasons, the central point stands: Operation Rough Rider placed a spotlight on the U.S. Navy's limited standoff strike capabilities.

It is important to recognize that this is a longstanding dynamic and is not limited to the U.S. Navy’s very long-range standoff land-attack capabilities. As noted earlier in this post, the AGM-158B JASSM-ER is being integrated onto the U.S. Navy’s F/A-18E/F strike fighter, and both the U.S. Navy’s F/A-18E/F and F-35C fighters can make use of the potent GBU-53 unpowered glide bomb, which is equipped with a rather exquisite tri-mode guidance system. The U.S. Navy is, however, well behind the U.S. Air Force in other respects for reasons of its own doing.

While the U.S. Air Force makes extensive use of the fairly inexpensive GBU-39 guided glide bomb, which can be readily used to attack targets located 50 or more kilometers from the launch aircraft, the U.S. Navy decided against procuring the GBU-39 and, more importantly, integrating it onto its carrier-based aircraft only to reverse course in 2025 once the qualitative and quantitative limitations of its strike capabilities were laid bare during operations against Ansarallah. Although the U.S. Navy’s unpowered AGM-154 JSOW guided glide bomb is a highlight of its standoff strike munition arsenal—the AGM-154C is, in effect, an unpowered cruise missile equipped with an imaging infrared seeker much like the powered AGM-158 JASSM family—the U.S. Air Force does not operate the AGM-154 JSOW and the two American military services are, as such, unable to maximally benefit from economies of scale in procurement. The U.S. Navy had previously pursued a powered version of the AGM-154 JSOW known as the JSOW-ER, but this development effort was abandoned prior to deployment, with the U.S. Navy deciding to instead integrate the AGM-158B JASSM-ER on its F/A-18E/F fighter fleet.

All things considered, the contemporary U.S. Navy is experiencing the legacy of a decision it made alongside the U.S. Air Force in the early 2000s to exclusively deploy the ubiquitous JDAM guidance kit in an unpowered configuration, which is in practice limited to a maximum range of 20-30 kilometers, and to forgo procurement of the privately developed JDAM-ER, which incorporates a wing kit and thereby amounts to a guided glide bomb. While the JDAM-ER has been exported and employed by the Ukrainian Air Force in the Russia-Ukraine War following an expedited—albeit partial—integration effort that puts the U.S. Navy to shame, there are currently no plans for either the U.S. Navy or the U.S. Air Force to procure the JDAM-ER. Resources are, of course, limited and must be prudently allocated toward a wide range of capabilities that amount to a coherent and synergistic capability set. While the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Air Force seemingly continue to hold the view that the JDAM-ER is not the right munition for them in light of their requriements and the other munitions that exist in their respective capability sets, it is important to recognize that U.S. military does not always make the best decisions and that it regularly backtracks on its previous decisions. The U.S. Navy’s belated about-face on integrating the GBU-39 onto its F/A-18E/F fighter fleet is a particularly salient example of this dynamic.

In the absence of a qualitatively and quantitatively more suitable array of strike munitions, the U.S. Navy appears to have heavily relied upon large but nevertheless finite stocks of:

RGM-109/UGM-109 Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles, which remain in production but are required in very large numbers for use in a potential war with China.

AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER air-launched cruise missiles, which are not in production and are unlikely to be brought back into production.

AGM-154 JSOW, which the U.S. Navy has not procured since the 2010s. With the U.S. Air Force not operating the AGM-154 JSOW and given evolving requirements vis-a-vis China in particular, the U.S. Navy is likely to shift procurement Dollars toward more expensive, longer-range munitions like the AGM-158B JASSM-ER going forward.

GBU-53 unpowered guided glide bombs, which are in production but are expensive by virtue of having a rather exquisite tri-mode guidance system that was likely excessive for use against many of the potential targets encountered in Operation Rough Rider. It is important to note that the GBU-53 only reached Initial Operating Capability (IOC) in 2020 and that it was only integrated on the U.S. Navy’s F/A-18E/F fleet in October 2023, which is to say just in time for the start of regular combat operations against Ansarallah.

The U.S. Navy may have also employed around 27 AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship cruise missiles against Ansarallah, presumably due to the unavailability of AGM-158B JASSM-ER land-attack cruise missiles for use by carrier-based F/A-18E/F fighters due to the potential non-integration of this missile in time for Operation Rough Rider. As a result, the U.S. military appears to have employed U.S. Air Force F-15E strike fighters operating out of Jordan to launch up to forty-four AGM-158 JASSM family land-attack cruise missiles against Ansarallah—perhaps more, and more generally turned to B-2 bombers forward-deployed to Diego Garcia to attack targets that the U.S. Navy’s strike munitions was presumably unsuited against in qualitative and/or quantitative terms.

Beyond the obvious implications of the apparent expenditure of large numbers of scarce standoff land-attack strike munitions during Operation Rough Rider and in preceding strikes against Ansarallah for the fast-evolving U.S.-China military balance, the United States faced the inherent risk of exposing its latest strike munitions to its adversaries in the absence of qualitatively and/or quantitatively suitable alternatives. The employment of the GBU-53 guided glide bomb in Operation Rough Rider is a case in point, given the fact that at least one specimen crashed in a fairly intact state (i.e., without detonating upon impact with the ground). The GBU-53 features a fairly exquisite tri-mode seeker that includes a millimeter wave active radar homing seeker that America’s adversaries will likely go to great lengths to access. Should the crashed GBU-53 specimen(s) not have been recovered and/or destroyed, the U.S. military faces the prospect of adversaries being far better positioned to develop countermeasures and more generally emulate the design of the GBU-53’s tri-mode seeker on their own munitions going forward.