Note: This concepts-themed post engages in inherently somewhat speculative analysis. I contend that any serious analysis must engage with the world both as it is and as it can be. Avoiding mindless empiricism requires cognizance of what is and what is not within the realm of possibility. Concepts-themed posts engage in this type of analysis.

In a recent post, I explained how a currently postponed mutual defence treaty between Australia and Papua New Guinea highlights the growing military challenges that China faces. Simply stated, China’s long-range conventional strike capabilities remain inadequate in both qualitative and quantitative terms for the type of conflict that China is increasingly likely to encounter in the Western Pacific, one in which the United States, Australia, and perhaps other countries are likely to operate from very distant bases in Papua New Guinea and elsewhere in the South Pacific more generally.

As I explained in the above post, targeting the likes of Lombrum naval base, which is located on the Papua New Guinean island of Manus, or the nearby Momote airport, both of which are located some 4300 kilometers from the Chinese mainland, is an example of an undertaking that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is not currently well-positioned to undertake, not least in a protracted conflict scenario that extends for months, if not years. While the PLA appears to have so far decided against pursuing low-cost long-range strike munitions in the manner of Iran and, more recently, Russia, for reasons that are not public knowledge, observers should recognize that such a development lies well within the realm of possibility. A long-range propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drone in the vein of the Iranian Shahed-136 design that can reach the southern Pacific from the Chinese mainland, and a very long-range cruise missile more generally, does not, however, constitute the only option(s) that China may pursue.

China has the option of using its manmade reefs-turned islands in the South China Sea, namely Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, and Mischief Reef, the latter of which is located some 3750 kilometers from Mischief Reef, as forward launch points for various strike munitions, including propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drones and very long-range cruise missiles. China can, of course, more generally employ air-launched strike munitions from launch points far out into the South China Sea and can similarly employ surface ships, including but not limited to PLA Navy warships, as forward launch points for various strike munitions. The PLA does, however, have another option available, one that will allow it to employ smaller, lighter, shorter-range, less expensive, and, all else being equal, more plentiful strike munitions.

Such an approach will require a forward launch platform that can get closer to the South Pacific than Mischief Reef and any Chinese surface ship or aircraft that respects the territorial waters and airspace of the Southeast Asian countries that are likely to remain neutral in time of war. The most straightforward way that the PLA can go about this is to employ a specific type of fairly large long-range uncrewed surface vessel (USV) and, going forward, perhaps a large uncrewed underwater vehicle (UUV) of the diesel-electric variety that primarily operates as a submersible running on the surface in the manner of most submarines through the early Cold War.

I have discussed how China may use USVs and UUVs as forward launch platforms equipped with various strike munitions against Taiwan in several recent posts:

China has the option of using long-range USVs, and perhaps long-range diesel-electric UUVs, to transport long-range strike munitions such as a propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drone(s) or a cruise missile(s) into the Sulu Sea, the Celebes Sea, and perhaps further out into the Pacific Ocean. A launch point near the easternmost parts of the Celebes Sea, south of the large Philippine island of Mindanao, will bring Lombrum naval base on the island of Manus, Papua New Guinea, within a range of around 2500 kilometers. There are propeller-driven strike drones and even long-range cruise missiles in existence that can cover such distances, albeit with a fairly modest warhead, given the payload-range constraints encountered at a low price point.

To reach the aforementioned notional launch point near the easternmost parts of the Celebes Sea, a Chinese USV or UUV, will need to travel some 1300 kilometers from Mischief Reef, one of China’s three largest reefs-turned-islands, or some 2450 kilometers from the PLAN bases located on Hainan. These are, of course, one-way distances, and a reusable USV will, as such, require a maximum range of at least 2600-4900 kilometers to reach the notional launch point from said starting points. The largest Ukrainian USVs, which are, of course, built for use in the confined waters of the Black Sea in general and against targets located some around the Crimean Peninsula, which is to say within some 300 kilometers of Ukrainian-controlled coastline, in particular, are reported to have a maximum one-way range of 800-1000 kilometers. A Chinese USV used to launch strike munitions against targets in the South Pacific will require a much greater maximum range, but, importantly, does not require the fairly high cruise speed of Ukrainian USVs that must attempt to evade Russian aerial and naval patrols as they approach Crimea, let alone the very high maximum speed required to have a higher probability of ramming into moving Russian warships. A Chinese long-range USV operating at a much lower and far more fuel-efficient cruise speed is very much within the realm of possibility.

All else being equal, the longer the maximum range of a USV, the greater its utility as a forward launch platform for various strike munitions. In an ideal world, a Chinese USV would navigate all the way toward a launch position located some 20-30 kilometers from a distant target like Lombrum naval base and launch multiple—perhaps several dozen—short-range, small, and light strike munitions—perhaps even armed multirotor drones. While such a USV is, in principle, possible, this is unlikely to amount to a very practical operational concept for China. There are, of course, also intermediate options that will only require a Chinese USV to reach a launch area located some 500-1000 kilometers from the intended target. Such distances are something of a sweet spot when it comes to low-cost propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drones and cruise missiles. A fairly light and, crucially, compact propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drone in the vein of the Iranian Shahed-101 and Shahed-107 comes to mind. These are designs that can be used to deliver a 15-20 kilogram warhead over a distance of at least 500-1000 kilometers.

It bears emphasis that while something in the vein of a 30-50 kilogram class warhead, let alone a 15-20 kilogram class warhead or a 5-10 kilogram class warhead, will have limited destructive effects and a limited destructive radius, such warheads are sufficient to, for example:

Severely damage, if not destroy, electrical generators.

Severely damage, if not destroy, the limited number of cranes used at small ports, including mobile truck-mounted cranes.

Severely damage, if not destroy, key nodes of airport infrastructure, including weather radar, above-ground fuel storage and pumps, and airport firefighting equipment.

Severely damage, if not destroy, the small numbers of heavy construction machinery that are likely to exist on most small, highly economically underdeveloped islands in the South Pacific. Such attacks would be aimed at slowing down, if not wholly thwarting, the establishment of military facilities.

Severely damage, if not destroy, equipment at aggregate quarries, concrete and asphalt production equipment/facilities, and so forth. Such attacks would be aimed at slowing down, if not wholly thwarting, the establishment of military facilities.

Target forward-positioned munitions and other military supplies. The South Pacific is a harsh environment for most types of military equipment, many of which must be stored in a certain temperature and humidity range without constant exposure to rainfall. Given this, targeting extant warehouses and similar structures can impede the buildup of American and Australian military forces across the South Pacific.

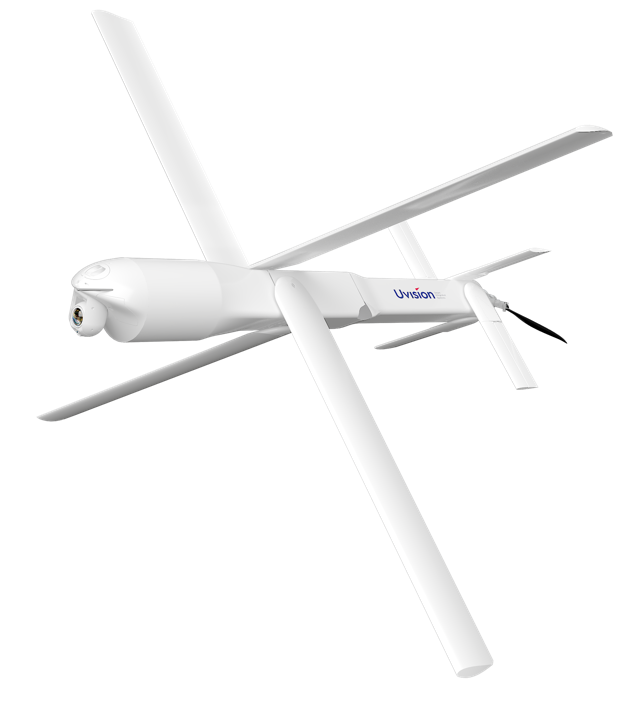

In this post, I set out to highlight one of the appraoches that China may pursue to expand the reach of its strike capabilities and, more importantly, expand the number of distant targets that it can attack, in a world in which the likes of Australia, the United States, and perhaps other countries are increasingly likely to make use of the limited terrestrial real estate available in the Pacific Ocean during a war with China. As things stand, China’s long-range conventional strike capabilities remain inadequate in both qualitative and quantitative terms for the type of conflict that China is increasingly likely to encounter in the Western Pacific. China can, however, take advantage of a range of recent and ongoing technological developments to attack very distant targets like Lombrum naval base on the Papua New Guinean island of Manus in new ways. I will conclude this by sharing an image of an American USV design tested by the American military, which is used as a forward launcher for Israeli HERO 120 propeller-driven fixed-wing loitering strike drones, a design that can also be used as a fire-and-forget non-loitering strike drone to attack stationary targets located some 60 kilometers away when equipped with a 4.5-kilogram warhead. While there is presently no publicly available information indicating that the PLA has pursued or is pursuing USVs and/or UUVs to attack very distant terrestrial targets, observers should be cognizant that such an approach to long-range strike is not only very much within the realm of possibility but may arise during wartime even if it does not exist in the PLA arsenal at the outset of a conflict.