Putting The "War" In Warship

🇨🇳 🇵🇭 Fratricidal collision highlights risk-taking, recklessness, escalation risk, and a Chinese warship commanding officer and crew mentally prepared for battle

On 11 August 2025, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) Type 052D-class destroyer Guilin (#164) collided with the China Coast Guard (CCG) patrol vessel #3104, which is an ex-PLAN Type 056-class corvette. The PLAN and CCG vessels were engaged in what amounted to a fairly routine unarmed tussle in the disputed waters of the South China Sea with the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) patrol vessel Suluan (#4406). In what appears to have been a failed maneuver intended to either ram the PCG vessel or at least box it in between the PLAN and CCG vessels, the PLAN destroyer ended up ramming the CCG vessel in the latter’s bow section. The fratricidal collision resulted in very significant damage to the CCG vessel and seemingly minor (external) damage to the PLAN warship. There are no reports of the loss of life as of this writing.

Much can be said of this fratricidal collision in the South China Sea, including what appears to have been a narrow avoidance of an incident in which the PLAN destroyer could have perpendicularly rammed the PCG vessel amidship, which may well have resulted in such catastrophic damage that the PCG vessel may have sunk—likely with the loss of life. Had such an incident transpired, the actions of the commanding officers and crew of the PLAN destroyer and CCG patrol vessel may have placed China on a collision course with the United States, which has a mutual defence pact with the Philippines. Stated differently, we may have witnessed a narrow brush with what could have been a very significant U.S.-China crisis in the South China Sea that has been avoided over the past fifteen or so years. It bears emphasis that the Philippine patrol vessel Suluan is a far smaller vessel than either of the Chinese vessels that collided with one another. The PCG’s Suluan displaces some 320 tonnes, the CCG’s ex-PLAN Type 056-class corvette #3104 likely displaces some 1400 or so tonnes, and the PLAN’s Type 052D-class destroyer Guilin displaces some 7500 tonnes. What did not transpire would not have been a collision of equals, and the fratricidal damage to the CCG’s bow seen in the above video would likely pale in comparison to the damage that the much smaller Philippine vessel would have been inflicted had the Chinese destroyer rammed it amidship just moments earlier.

While this post can join the chorus of commentary on potential issues with Chinese maritime command and control and coordination between the PLAN and CCG, the seamanship of involved PLAN and CCG personnel, the risk-taking—if not outright reckless—behaviour regularly undertaken by the PLA and the CCG (as well as the Chinese Maritime Militia), and Beijing’s longstanding unwillingness and/or inability to put in place robust guardrails to avoid such incidents, I think there is a far more important observation to be drawn from this incident and others like it. The commanding officer and the crew of the PLAN destroyer Guilin evidently went to sea mentally prepared for war—to sustain damage, to suffer casualties, and to die at sea if necessary. Stated differently, the Chinese destroyer Guilin and its crew put the “war” in warship.

One of the most peculiar dynamics regularly observed along China’s maritime frontier is that Chinese military—and paramilitary—personnel regularly undertake high-risk—if not outright reckless—actions at sea and in the air. This includes high-risk interceptions of foreign military aircraft, which sometimes result in the deployment of flares, and high-risk interceptions—and some clear-cut ramming attempts—at sea. In April 2001, one such interception attempt by a PLAN J-8 interceptor aircraft resulted in a collision with a U.S. Navy EP-3 electronic intelligence aircraft over the South China Sea. While the damaged EP-3 aircraft made a successful emergency landing on the Chinese island of Hainan, the J-8 interceptor aircraft crashed, and its pilot was killed.

Foreign observers are often publicly appalled at the conduct of Chinese military—and paramilitary—personnel in the aftermath of such incidents. After repeated incidents in which Chinese personnel are said to have directed lasers toward foreign military aircraft, which can damage the eyesight if not blind the occupants who happen to be looking toward the source of the emitting laser, foreign observers have tended to characterize such Chinese conduct as unacceptable because, the publicly expressed logic goes, foreign military personnel “are just doing their jobs” and country x is not at war with China.

The publicly expressed sentiment that country x is not at war with China is, of course, true, and the moral appeal of “professional conduct” so as to avoid “unnecessary loss of life” among military personnel who are “just doing their jobs” is, of course, also understandable. And yet, the humans crewing the vessels and aircraft of all involved countries, including those of China, are agents of governments who willingly engage in competitive risk-taking and place their military personnel in harm’s way. No one professionally involved in such incidents should be under the illusion that they are not (often volunteer and financially compensated) pawns in much bigger games of competitive risk-taking. Moreover, the jobs of foreign military personnel are, like the jobs of Chinese military personnel, to train in preparation of killing foreign military personnel while accepting the risk of being killed themselves (while not all military personnel are in positions that will likely lead to active combat roles in time of war, all military personnel exist to support organizations that are intrinsically defined by preparation for the killing of opposing military personnel). There is, as such, something profoundly incongruous about complaints against the use or threatened use of violence against military personnel in situations that fall short of an outright and clear-cut armed conflict. A military pilot who is mentally unprepared to die in flight due to a mechanical problem or adversary action has not found an appropriate vocation, and the commanding officers and crew of a warship who are mentally unprepared to die at sea have forgotten that they are not tourists aboard a cruise ship.

PCG vessels sail into the South China Sea to enforce what Manila claims—with widespread international backing—to be the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone. PCG vessels purposefully and willingly engage in regular tussles with PLAN, CCG, and Chinese Maritime Militia vessels, knowing full well that a collision or other incident may risk the loss of a vessel, injuries, and even the loss of life. They do not do so only out of a sense of patriotic duty, in exchange for salaries, and out of respect for their chain of command, but because they are the latest crop of willing pawns for the Philippine government in the complex game that has been playing out in the disputed waters of the South China Sea for several decades.

While Beijing dispatches PLAN, CCG, and Chinese Maritime Militia vessels to the disputed waters of the South China Sea to coerce rival claimants into acquiescing to China’s expansive maritime claims and employs its own pawsin competitive risk-taking at sea, Manila is enggaged in the same complex game but is going about it in a very different way and with highly variant resources at its disposal. The single-greatest asset on the Philippine side of the ledger is that the country has a mutual defence pact with the United States. Given this, the Philippine government has been increasingly emboldened in its actions over the years and appears to be increasingly confident—emboldened—in sending out naval and coast guard vessels into the South China Sea despite the risks inherent to doing so established by China’s longstanding modus operandi in the waters that it contests.

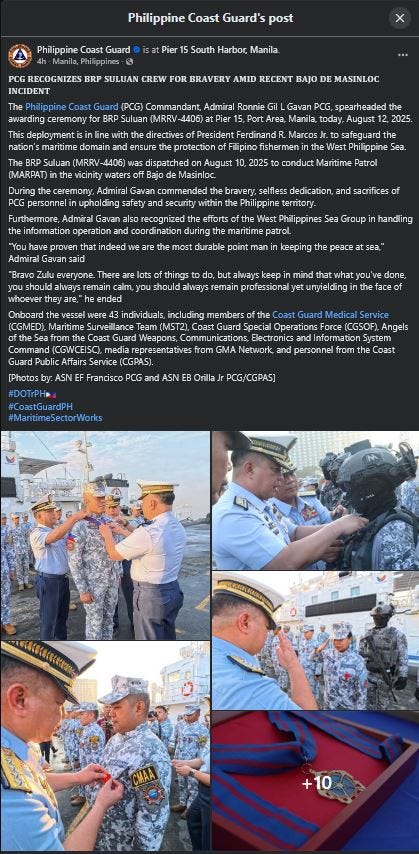

The Filipinos who unwittingly had a narrow brush with major injury and possible death on the PCG patrol vessel Suluan on 11 August 2025 were not random Filipinos going about their everyday affairs across the archipelagic country; they knew exactly what they were doing in this latest of routine tussles at sea—it takes two to play such a “game.” It is important to note that the PCG crew were purposefully filming this and other encounters with Chinese vessels—the only publicly available recordings of the fractricidal collision come from persons aboard the PCG patrol vessel Suluan. Tellingly, the PCG crew—understandably—cheered (at 00:34) in the immediate aftermath of the fratricidal collision between the Chinese vessels, a dynamic which likely explains why much of the audio was removed (such as at 00:19) before the video was uploaded as part of Manila’s—understandable and so far highly effective—public relations efforts. While Manila went out of its way to highlight how the PCG’s Filipino crew offered the stricken Chinese CCG vessel assistance in the aftermath of the fratricidal collision as part of such public relations efforts, the Philippine government quickly awarded the crew of the PCG patrol vessel Suluan medals once the vessel returned to a port in Manila Bay. The Filipino crew went to sea mentally prepared for such an incident and was very fortunate to return to port unscathed.

It is important to note that this is not an exclusively China-Philippines dynamic; the intensifying military-technological competition in the Western Pacific has many competitors, most of whom are either formally or informally aligned against China and are, as such, reciprocating China’s (peacetime) preparations for war. The American and Australian aircrews—and those of other nationalities—that are aboard maritime patrol/anti-submarine warfare aircraft patrolling the South China Sea and elsewhere know full well that the onboard sensors that these aircraft exist to relocate and employ—the (active) surface search radar, passive electronic/signals intelligence gathering receivers, the multi-band sensor ball, and, not least, the air-dropped sonobuoys and onboard processing equipment—all exist to collect vital intelligence on Chinese warships and submarines that will be used to improve the effectivness of various types of military equipment against these systems and improve the effectiveness of coutermeasures against various types of Chinese military equipment (which will, in turn, make Chinese warships and submarines more vulnerbale to attack).

And yet, political leaders and other officials tend to publicly characterize what are undeniably high-risk and, in some cases, even reckless conduct on the part of Chinese military and paramilitary personnel as if their own military personnel were not operating in forward areas with the primary objective of helping their militaries more effectively destroy Chinese ships and aircraft and, in so doing, injure and kill Chinese military personnel—including the very Chinese personnel undertaking these high-risk if not outright reckless actions. It is no exaggeration to say that the high-risk—if not outright reckless—actions of the Chinese pilot in the following video recorded by an American P-8 maritime patrol/anti-submarine warfare aircraft over the South China Sea and similar Chinese actions may end up saving the lives of Chinese military personnel in a future conflict.

To be clear, commentary about unsafe and unprofessional—if not outright reckless—conduct on the part of PLA personnel (and those of the CCG and Chinese Maritime Militia more generally) is wholly understandable if it is solely undertaken as part of public relations efforts. If, however, policymakers and their intended audiences actually believe in their public rhetoric, there will exist a fundamental misunderstanding of what military personnel are paid to do and exist to do: to kill if ordered to do so and to be killed if required. Military personnel are not in positions analogous to everyday “9-5” jobs—they are the armed agents of governments who regularly and willingly place their own military personnel in harm’s way in opposition to their Chinese and other counterparts who are doing much the same.

While the video released by the Philippine Coast Guard amounts to incredible footage in more ways than one, perhaps the single most notable aspect of the video is not the fratricidal collision itself but the reaction of the Chinese destroyer Guilin in its immediate aftermath (from ~00:43 onward in the video, which is embedded once more below for the convenience of the reader). Uncertainties notwithstanding, the only publicly available video of this incident indicates that the Guilin did not attempt to come to a full stop in the immediate aftermath of the fratricidal collision in which it was involved. After undertaking belated evasive maneuvers, it continued to pursue the PCG patrol vessel Suluan and then proceeded to undertake another attempt to ram the Philippine vessel. This is, of course, in a context in which CCG personnel—particularly those exposed on the upper deck at the time of the collision—are likely to have been injured and possibly thrown overboard. The commanding officer of the Chinese destroyer Guilin appears to have only checked to see if the ship’s propulsion system remained online and the rudder was responsive. With those two fundamental conditions having seemingly been met, the commanding officer of the Guilin seemingly proceeded with the mission in much the same manner that warship crews must conduct themselves in time of war even when their colleagues in nearby ships are in need of aid and their even as their own ship may have been damaged with casualties among their fellow crewmembers. The commanding officer and crew of the Guilin are aboard a warship—not a cruise ship—and conducted themselves accordingly in the immediate aftermath of the fratricidal collision in which they were directly involved.

To be clear, mindless aggression is unlikely to be a consistent recipe for success in wartime. There is, however, a case to be made for calculated and deliberate aggression in martial affairs when it is combined with skill and competitive equipment and activated in advantageous and opportune contexts. As with most things in life, situational moderation is in order, and calculated and deliberate aggression has its time, place, and purpose. One of the biggest challenges that militaries have always faced is conditioning everyday people—the population from which military personnel are hired—to rapidly shift into a state of mind in which they are ready to both kill and be killed. Needless to say, militaries rarely want to condition their personnel into truly mindless killing machines, given the need for consistent subordination and the requisite ability to kill when commanded and not kill—and potentially risk injury and death—when commanded not to do so. On 11 August 2025, the conduct of the commanding officer and crew of the Chinese destroyer Guilin in the fratricidal collision exhibited many things, both good and bad, about the PLAN as a military organization—an organization that is intrinsically defined by preparation for the killing of opposing military personnel. There is a case to be made that the commanding officer and crew of the Chinese destroyer put the “war” in warship in the immediate aftermath of the fratricidal collision, even as their high-risk—if not outright reckless—conduct appears to have resulted in a narrow brush with a China-United States crisis in the South China Sea in which such calculated and deliberate aggression would be very much be in order.