Some Thoughts On Taiwan's Latest Civil Defence Handbook As It Pertains To A Chinese Invasion Scenario

🇹🇼

Taiwan has released the 2025 edition of its civil defence handbook. I have reviewed the official English language version and have some thoughts. Anyone interested in how a Chinese invasion of Taiwan may play out must be mindful that the 23 million or so persons residing on the island are part of the human terrain. In times of crisis and war, humans who are afraid, injured, hungry, and so forth will behave in unpredictable ways, ways that may even be harmful to their own country’s war effort. As a result, governments that take war/invasion preparations seriously are incentivized to mentally prepare everyday people as much as they are incentivized to prepare their military personnel for combat. Analysts and observers interested in a Taiwan invasion scenario should, therefore, take note of the latest edition of Taiwan’s civil defence handbook.

Assumptions About Connectivity

All things considered, the handbook offers Taiwan’s inhabitants useful information not only for times of crisis and war but also for natural and manmade disasters. One of the most striking aspects of the document is the inherent assumption it makes about the state of connectivity in times of crisis and war. The document features many QR codes, phone numbers, and URLs that can only be accessed in a situation in which mobile phone coverage and internet access essentially remain at pre-war levels. This is an increasingly questionable assumption given trends in military technology, the evolution of China’s military capabilities, and the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) incentives to degrade Taiwan’s inherently dual-use communication infrastructure in time of war, particularly during and after an amphibious invasion attempt.

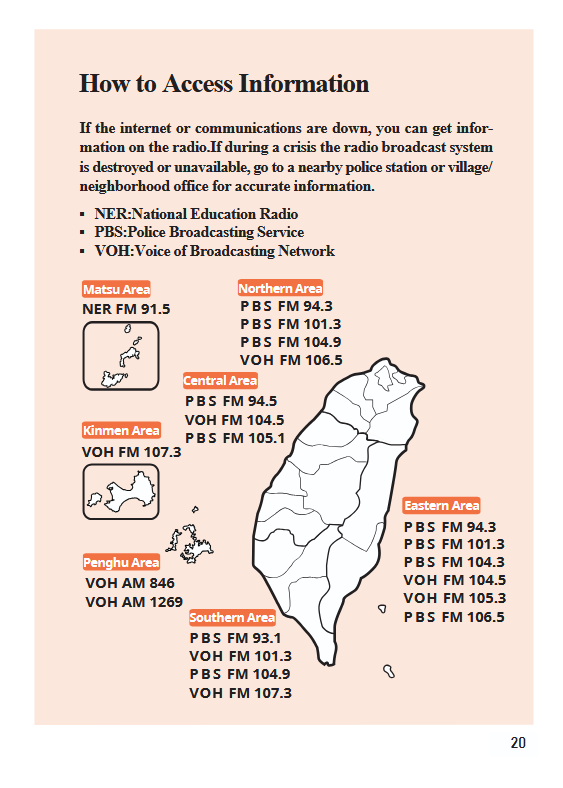

Taiwanese decision-makers are, of course, aware of this dynamic and have been working to bolster the resilience of the island country’s telecommunications infrastructure. While China will likely be unable to fully cut Taiwan off from the (worldwide) internet—it may, however, target the landing stations of the submarine internet cables that connect Taiwan to the (worldwide) internet—let alone Taiwan’s internal terrestial “intranet” network, at least short of a protracted conflict scenario in which most Taiwanese lose access to electricity, China is increasingly well positioned to target radio transmission facilities across Taiwan. By radio transmission facilities, I do not only refer to AM and FM radio but also cellular communication towers and microwave relay antennas, the latter of which are extremely important in the mountainous areas of Taiwan.

While there are some workarounds that Taiwan may pursue following widespread PLA strikes targeting Taiwan’s telecommunications infrastructure, there is no full substitute to the high-elevation transmission equipment installed on towers and at high elevations in peacetime. Taiwan may use apartment buildings and other high-rise structures as wartime radio transmission sites, but these transmissions can be detected, and it has never been easier for China—or any other military—to target such transmission sites. It is worth noting that technological trends mean that China need not raze, for example, an apartment building to neutralize a radio transmitter placed on its roof. The PLA can very “surgically” target such transmission equipment with fairly small and light munitions. While Taiwan will likely undertake constant efforts to reconstitute its telecommunication efforts in wartime in the face of sustained Chinese attacks, much of the island is likely to be operating with highly degraded connectivity. Stated differently, many of Taiwan’s inhabitants are likely to remain beyond the reach of Taiwan’s senior-most decision-makers in Taipei.

What To Do—And Not Do—If Taiwan’s Residents Spot PLA Personnel/Vehicles

Somewhat surprisingly, the document has relatively little to say when it comes to advising Taiwan’s inhabitants on how they should conduct themselves during and after a PLA amphibious invasion attempt.

The document advises Taiwan’s inhabitants to “leave the area as quickly as possible” when spotting possible PLA activity. This is, of course, reasonable advice, but it is also a recipe for chaos and congested roads. Civilians rushing out of an area on foot, by bicycle, and by car will impede Taiwanese military traffic in wartime. Amid the chaos of war, there will doubtless be incidents in which, for example, a car packed with a family desperately trying to get away takes what they hope to be a shortcut, only to run into a PLA column. PLA personnel could be given the exact same training on the laws of war and related issues as Western militaries—or the Taiwanese military itself, but the unfortunate reality is that the results are likely to be more or less the same: PLA combatants—who are likely to be extremely fatigued and running on adrenaline—will likely point their weapons and, at least, fire a few shots as a warning with all too predictable results.

All things considered, the best advice to all civilians in any conflict zone is to shelter in place—away from windows—for as long as possible and, in effect, stay out of it so as to unambiguously remain a non-combatant. This, of course, means obeying reasonable demands from occupying military forces and occupying civil administrators, however begrudging such obedience may be. The primary exception will be in cases in which there is a reasonable expectation that civilians who shelter in place will be massacred by enemy forces, irrespective of their conduct. If the Taiwanese government thinks that massacres by PLA forces are likely, it would do well to communicate as such in advance so as to avoid the chaos and congestion that will likely result—with or without guidelines of one sort or another—in times of crisis and war. Moreover, it would do well to systematically evacuate outlying areas, particularly the sections of the coastline that are candidates for a PLA amphibious landing, in advance.

It bears emphasis that while a full-scale PLA amphibious invasion of the island of Taiwan proper may not be very likely, the same cannot be said about a full-scale PLA amphibious invasion of Taiwan’s Kinmen and Matsu Islands, the Penghu Islands, and other outlying Taiwanese territory more generally. One would think that the inhabitants of those islands, who, for all practical intents and purposes, cannot escape, require very different advice from their government than the inhabitants of the island of Taiwan. Similarly, persons who reside along Taiwan’s western coastline require very different advice from their government than the inhabitants of other parts of the island, particularly persons who live in the country’s mountainous interior and along its eastern coast.

The document notably tells—not suggests—Taiwan’s residents not to “take photos or videos of the Taiwan military’s movements or upload or share that information, as it could put friendly forces in danger.” This is, of course, sound advice, but it could go much further. Civilians who take photos and videos of the aftermath of military activity, including air and missile strikes, unwittingly provide a lot of useful information to enemy forces. This may, of course, matter little if Taiwan’s telecommunications are heavily degraded—an island country that is disconnected from the worldwide internet is, by definition, an island country with a terrestrial, Taiwan-only intranet that cannot be readily accessed by China. This should serve as a reminder of how impactful the wartime state of Taiwan’s telecommunications infrastructure is likely to be on so many aspects of a war, given the insular (i.e., island) nature of the country.

It is notable but not entirely surprising that the Taiwanese government does not caution the residents of the island country against taking photos or videos of Chinese/PLA military positions and movements. While governments and militaries unsurprisingly and understandably want to receive such information—intelligence—in wartime, the civilians who take such photos and videos place themselves at risk, given how any person monitoring and reporting on enemy military activity is no longer a strict non-combatant irrespective of what they wear, their pre-war job/role, and whether or not they (self) identifiy as a combatant. War is not a game, certainly not a fair game, and even the best-trained and most-disciplined militaries are likely to fire upon nominal civilians who are monitoring and reporting on their movements. The Taiwanese government will place the residents of the island country at grave risk if it not only fails to explicitly caution against such activity but, in effect, implicitly welcomes it.

I have much more to say on this topic, not least as it relates to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War. Suffice it to say, wars are nothing like the idealized nineteenth-century battlefields in which opposing armies typically marched toward one another’s positions in open fields wearing bright—or at least unmistakably military with headgear, etc.—uniforms and more generally operating in a context in which there was little ambiguity between a combatant and non-combatant. This is the context, military, social, and otherwise, that informs the enduring laws of war and related. It is important to note that even in this quite brutal idealized nineteenth-century context, non-uniformed combatants, spies, and similar were widely held to be franc-tireurs and subject to summary executions following capture. While the laws and norms of war and related matters have evolved considerably since then, not least in the aftermath of the Second World War, there is a case to be made that technological change and changing military practices have outpaced the evolution of the laws and norms of war and related matters.

Given the tangent, I will offer a few examples that are relevant to Taiwan: (nominal) civilians reporting enemy military movements and positions on phone apps and similar created by one’s own government, (nominal) civilians operating camera-equipped multirotor drones in support of combatants, (nominal) civilians assembling munitions, whether so-called molotov cocktails or multirotor drones, and (nominal) civilians transporting military and/or military-related equipment, including general supplies and provisions, for (lawful) combatants. Taiwan’s government will do well to explicate its position on what it does and does not expect—even forbid—of the island country’s inhabitants in time of war.

The Uncomfortable Question Of Surrender

All things considered, the single most important—or at least the single most consequential—part of Taiwan’s latest civil defence handbook is found on page 19.

The official English-language version of the document states in no uncertain terms that “in the event of a military invasion of Taiwan, any claim that the government has surrendered or that the nation has been defeated is false.” The sentiment behind this statement is understandable, as is the instrumental logic of cautioning Taiwan’s inhabitants against readily accepting Chinese/PLA propaganda, disinformation, and so forth. And yet, such statements are fundamentally problematic and lack any nobility. There are only three alternatives to surrender in war: escape, which is not a viable option for the inhabitants of Taiwan and other island countries more generally; victory, which is ultimately the preferred and “simplest” option that need not be elaborated; surrender, which few are willing to countenance in advance but all must ultimately come to terms with, however begrudgingly; and death. Taiwan’s inhabitants cannot escape. The prospects for victory are undoubtedly non-zero, but will change if and when a PLA amphibious attempt is underway/has taken place. By unconditionally and unequivocally ruling out surrender in advance of a conflict, Taiwan’s government is telling the island country’s population… what exactly? Taiwan does not have nuclear weapons. It cannot “secure” its national survival by threatening to obliterate Chinese cities (even if it could, China can “absorb” far more nuclear attacks than Taiwan ever can, given the variance in geography and demography). The only alternative to surrender in the absence of escape or victory is death.

Personally, I think that governments should offer official advice on how their inhabitants should and should not conduct themselves in the event of being captured/being in enemy-controlled territory. If nothing else, it establishes clear expectations and limits on appropriate behaviour, a dynamic that facilitates clear understandings of what conduct will be punished, perhaps with execution, when the war comes to an end, as all wars ultimately do. Needless to say, the latest edition of Taiwan’s civil defence handbook never tells the country’s inhabitants that they should never surrender to the PLA or that they should resist—fight—to the death. It does, however, essentially say just that about what Taiwan will do as a country. What are Taiwan’s inhabitants to do in the event that the PLA controls the parts of the island country’s western coastal plain, which is where most of the population resides? If not surrendering, does the Taiwanese government expect its civilians to “keep fighting?” Does the Taiwanese government expect its civilians to wage an insurgency and support what remains of Taiwan’s uniformed military in such an insurgency? Does it expect its civilians to, for example, approach a Communist Party of China official in charge of administering their occupied town—or a Taiwanese person collaborating with the PLA and the People’s Republic of China more generally—to… do what exactly other than submit—surrender—while hoping and working for a better future in which Taiwan’s independence is restored?

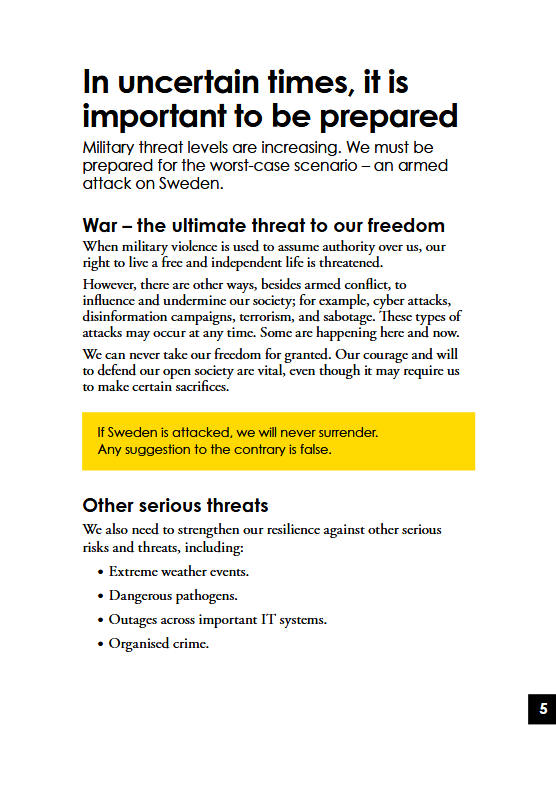

Taiwan is not the only country to make such grandiose statements in its civil defence handbooks. For years, Sweden was one of the few countries to openly express such a position. Consider the following text from the latest edition of Sweden’s civil defence handbook:

However noble such statements may appear, I would contend that such statements are irrational in much the same manner as Imperial Japan’s wartime “no surrender” policy. Surrender is always an option and in many cases becomes the residual least bad option, not least when the alternative is death. Telling the world—including your adversary—that you will never surrender makes for a grand statement, but may also (re)shape how your adversary will pursue its war.

For Sweden in the Cold War, the official “we will never surrender” position arguably made some sense. The most plausible scenario in which Sweden would face an invasion from the Soviet Union would be an all-out conflict between the Warsaw Pact and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) across Europe. Such a conflict would have likely seen the use of hundreds, if not thousands, of so-called “tactical” nuclear weapons against battlefield targets, airbases, and so forth, even if the Soviet Union and the United States did not target one another’s territory with so-called “strategic” nuclear weapons. The Swedish government’s objective was to avoid being caught up in such a conflict, and part of that entailed preparing Swedish society to, in effect, fight to the death to avoid being occupied and ultimately perhaps ruled by the Soviet Union. In the absence of Swedish nuclear weapons, Sweden’s “total defence” could serve as a deterrent against a Soviet invasion. It could not, of course, do anything to stop the Soviet Union from invading and occupying Norway or, perhaps more to the point, do anything to stop the Soviet Union, the United States, and their respective allies from turning Europe—perhaps the entire planet—into an unlivable post-nuclear hellscape.

Taiwan finds itself in a very different position than Sweden did in the Cold War—Sweden’s ongoing retention of such language makes little sense in the post-Cold War period, not least following the accession of both Sweden and Finland into NATO. While Taiwan does face an—politically—existential war with the People’s Republic of China, it does not face the oblivion of its population. Surrender is—and arguably must always remain absent a commitment to what amounts to a national suicide pact—an option. The best that Taiwan can do is to prepare itself such that Beijing decides against undertaking an invasion attempt or, failing that, ensuring that a Chinese invasion attempt fails. That requires real effort and the allocation of real resources, not cheap and irrational statements, as well as a deeply considered set of guidance and policies as to what is expected of Taiwan’s inhabitants in time of war and how they should and should not conduct themselves. The stakes are all too real and far too high for Taiwan to be cavalier about how the island country’s inhabitants should conduct themselves in time of war. Preparing for victory, mentally and otherwise, paradoxically requires open and meaningful discussions of what defeat entails and how defeat scenarios may play out.