Ukraine Resumes Strike Campaign Against Russia's Energy Infrastructure, Ukrainian Strike Drones Attack Refinery In Russia's Komi Republic

🇷🇺 🇺🇦

Ukraine recently initiated what appears to be yet another concerted strike campaign against Russia's energy—oil and gas—infrastructure. This notably includes the targeting of an oil refinery in Russia’s Komi Republic that is located around 1700 kilometers from the international border, around 1250 kilometers northeast of Moscow, and some 560 kilometers from the Barents Sea. While the Komi Republic—a province-type sub-national administrative unit—and other more distant Russian provinces had hitherto been beyond the reach of Ukraine’s long-range strike capabilities, prior modifications made to existing Ukrainian strike munitions and the apparent deployment of new strike munitions used in this latest attack have brought an expanding part of Russia’s vast but primarily uninhabited territory within the reach of Ukraine’s strike capabilities.

While the prior Ukrainian attacks against Russia’s energy infrastructure have had a decidedly non-zero effect on the Russian war economy and the country’s war effort, the employment of Ukraine’s fast-expanding and increasingly diverse array of long-range strike munitions, which is composed of a combination of Ukrainian-built propeller-driven (fixed-wing) strike drones and turbojet-powered cruise missiles, have offered Ukraine a means of inducing the dilution of Russia’s expansive but finite air defence capabilities across an increasingly large surface area (and punishing Russia’s failures to do so). As Ukrainian strike munitions—primarily its propeller-driven strike drones—have evolved in terms of nominal maximum range, Ukraine has not only been able to bring an ever-increasing number of potential targets—not limited to energy infrastructure—within range but also further dilute Russia’s air defence capabilities (this dynamic is best characterized as virtual attrition). In so doing, Ukraine has been able to enhance the effectiveness of its expanding strike capabilities against more proximate targets and, more generally, the physical indicators of destruction at Russian oil refineries and other energy facilities have offered Kyiv a useful tool in shaping public perceptions as to the course of the Russia-Ukraine War.

It goes without saying that prior Ukrainian campaigns against Russia’s energy infrastructure have not resulted in the collapse of Russia’s war economy or even its critically important energy industry. It is important to highlight several interrelated reasons why this was the case before examining the footage from the recent attack on an oil refinery in Russia’s Komi Republic.

Russia is home to a very large number of oil and gas facilities that are spread across much of western Russia, which is to say west of the Ural Mountains.

A specific energy facility, such as an oil refinery, is not a single small structure but the amalgamation of dozens, if not hundreds, of discrete structures that individually amount to discrete aimpoints. While only a subset of structures tend to be critically important, it is nevertheless important to recognize that dozens, if not hundreds, of munitions may be required to truly “destroy” such facilities.

While fuel tanks will typically burn for days following an attack, oil and gas infrastructure includes many industrial structures that can be quite resilient to low and moderate levels of damage and which can be repaired or, more generally, continue to operate at a degraded capacity.

As a result, some discrete aimpoints may require precise and accurate hits from multiple strike munitions to sustain severe levels of damage, let alone total destruction. The number of munitions required to severely damage or destroy such a facility is a function of weaponeering analysis and is naturally affected by the size/weight of the warhead installed on a strike munition, the precision and accuracy of a strike munition, its fusing mode(s), and the interplay of the aforementioned factors with the nature of a particular target.

Given the sheer number of discrete aimpoints in Russian energy facilities west of the Ural Mountains, Ukraine needs to launch a very large number of propeller-driven strike drones, some of which constitute Ukraine’s longest-range strike munitions, and/or turbojet-powered cruise missiles, which generally fall on the lower- and medium-end of the range spectrum. Ukraine only has a finite number of such strike munitions available at a given time and has so far primarily prioritized attacks on a greater number of targets over the concentration of large numbers of available strike munitions against a smaller number of targets.

Most Ukrainian strike munitions are fairly inexpensive and simple designs with limited payload— generally in the 10-30 kilogram class. Warheads—particularly generic high explosive-fragmentation warheads with impact fuses in this weight class—have a very limited destructive radius against forms of matter other than soft tissue. As a result, Ukrainian strike munitions can primarily damage, not destroy, the objects at discrete aimpoints. While multiple strike munitions can be used to target a single aimpoint, strike munitions are limited in supply. It is important to note that Ukraine has so far preferred to stretch its strike arsenal thin to attack a larger number of targets—this can be uncharitably characterized as Ukraine regularly prioritizing spectacle over substance—and that it is more efficient to use strike munitions that are equipped with larger warheads for such purposes. Simply stated, strike munitions with small warheads are generally more suitable for harassment strikes than destruction, although there are specific target classes against which even an otherwise modest 10-30 kilogram class high explosive-fragmentation warhead can be devastatingly effective.

Ukraine’s longest-range strike munitions, which are required to hit distant targets, such as the oil refinery in Russia’s Komi Republic, are more expensive and are likely to be available in limited numbers. It is important to note that the simplest and most inexpensive way to obtain a greater nominal maximum range in a strike munition without designing a new airframe and using a more expensive propulsion system is to trade payload for range, a dynamic that exacerbates the aforementioned dynamics that have affected prior Ukrainian campaigns against Russia’s energy infrastructure and other targets more generally.

While the penetration rate of Ukraine’s strike munitions is evidently greater than 0%, Russia’s air defences are far from being wholly impotent, and public information offers very limited insight as to how many strike munitions are launched by Ukraine in order for what is likely to be a small subset to reach their intended targets in Russia. Whereas there is a lot of decidedly imperfect publicly available information on Russia’s employment of strike munitions against Ukraine, the same cannot be said of Ukrainian strike munition employment against Russia. Observers should, as such, be extremely cautious when dealing with fragmentary information in this area.

For background on Ukraine’s employment of propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drones against Russia, consider reading one of my previous posts:

The 10 August 2025 Ukrainian attack targeted the Lukoil oil refinery located in the town of Ukhta, Komi Republic. As noted earlier, this refinery is located around 1700 kilometers from the international border, around 1250 kilometers northeast of Moscow, and some 560 kilometers from the Barents Sea.

Russians on the ground—presumably workers at the refinery —recorded the Ukrainian attack, which took place in daylight, with their mobile phone cameras. It is worth noting that the Ukrainian strike drone that reached the refinery likely had a flight duration of over eleven hours. That is, the Ukrainian strike drone was launched in darkness and penetrated Russian airspace in darkness—it is simply far too slow to reach such a distant target without encountering daylight, not least in the summer months and at such a high latitude.

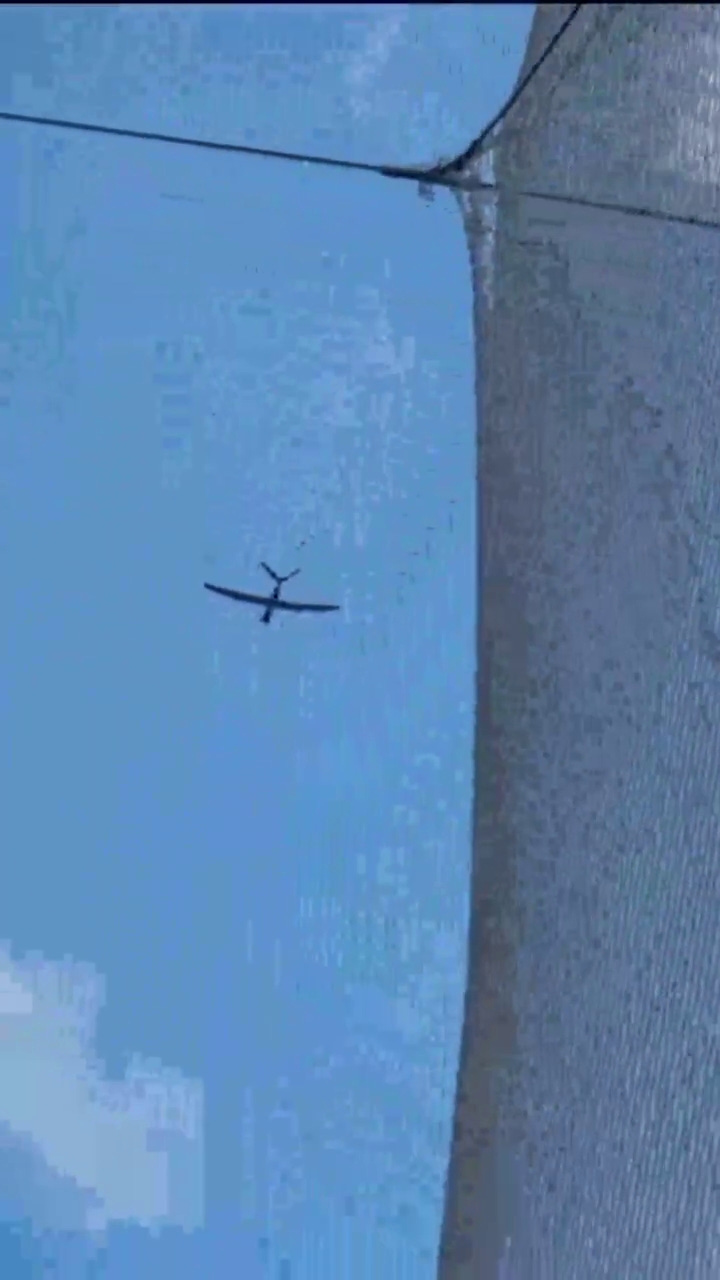

The following video shows one Ukrainian propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drone in flight. It bears emphasis that observers operating with publicly available information cannot discern whether Ukraine launched more than one strike drone to attack this particular target. As is often the case, observers operating with access to publicy available information are working with apparent numerators—the number of strike munitions that appear to have reached the apparent intended target—without being aware of the denominator—the total number of strike munitions that were launched with the purpose of attacking said target, which is to say the number that either failed in flight or were neutralized by Russian air defence activity and/or Russian electronic warfare (i.e., GNSS jamming and/or spoofing).

Several observations can be made on the basis of the above video. First, the audio does not offer any indication of anti-aircraft activity at the targeted oil refinery, which can be as rudimentary as manually-directed small arms and/or machine guns firing with the aim of either damaging the strike drone—which will result in large pieces of debris crashing into the ground somewhere nearby, possibly including an intact and functional live warhead—or ideally destroying the drone while it in flight by detonating the warhead and/or setting the fuel tank on fire—which will result in smaller pieces of debris crashing into the ground somewhere nearby. This is essentially the norm when it comes to such videos recorded near the presumed targets of Ukrainian strike munitions in Russia, which is to say that Russia does not appear to have allocated even a very rudimentary anti-aircraft capability across the vast expanse of its territory west of the Ural Mountains that is within the expanding reach of Ukraine’s fast-evolving arsenal of strike munitions.

Notwithstanding the fundamental differences in geography and the vastness of Russia’s territorial expanse, it is worth noting that Ukraine has put in place a far more effective approach to rear area air defence, an important topic that I covered in a recent post:

Second, the video indicates the presence of passive defences in the form of protective nets at this facility. Various protective structures of this type have been installed at energy facilities and other potential targets across western Russia. Propeller-driven strike drones generally have a maximum speed of around 200 kilometers per hour. Given the small size of the warhead carried by most examples of such strike munitions, the destructive radius is very limited, and a “premature” detonation—such munitions typically have impact fuses—located meters from the intended target can greatly reduce the damage sustained by the intended target and nearby structures. This is particularly the case with targets such as oil tanks that are used to store combustible material—the secondary destructive effects caused by a fire are often far greater than the primary destructive effects caused by the detonation of the high explosive warhead itself.

Third, the video suggests that Ukraine employed a new—previously unseen—propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drone design. This particular strike drone design:

Does not appear to be equipped with fixed landing gear, which is a peculiar characteristic of several of the propeller-driven strike drone designs in Ukraine’s arsenal.

Has a distinctive V-shaped tail.

Has fairly high aspect ratio wings.

Given the fact that the targeted oil refinery is located some 1700 kilometers from the international border, this appears to be a purpose-built long-range propeller-driven strike drone design, unlike most of Ukraine’s strike drone designs, some of which have been been modified for greater range by trading payload for range (i.e., using a smaller/lighter warhead and a larger fuel tank).

All strike munitions have a nominal maximum range that is best understood as nominal range-endurance that is reflective of a specific range-payload tradeoff selected by the designers. There tends to be some (limited) scope to trade range for payload, which is to say install a smaller and lighter warhead in exchange for a larger fuel tank (and vice versa). The size and weight of the warhead installed on this previously unseen Ukrainian strike drone design are not public knowledge as of this writing. There is, however, a video circulating on Telegram that purports to capture the damage resulting from this particular attack against an oil refinery located in Russia’s Komi Republic. The following video suggests that the Ukrainian strike resulted in very limited damage against at least one oil storage tank that was notably not protected by the protective netting seen in another video purportedly recorded at this Russian oil refinery.

There is no indication of a large fire on the open-source NASA FIRMS portal, which is to say that this particular attack on a Russian oil refinery has not resulted in one or more oil tanks catching fire and burning for days.

As a result, this unprecedented attack against a Russian oil refinery in the distant Komi Republic appears is best understood as not only a sign of things to come if the Russia-Ukraine War continues on its present trajectory but also the enduring challenges that Ukraine’s long-range strike campaigns face as well as Ukraine’s enduring prioritization of spectacle over substance in this area. Time will tell if Ukraine can replicate such spectacles going forward and, more generally and more consequentially, increase the substantive effects of such distant strikes on the Russian war economy and Russia’s war effort more generally.