Will The Gulf Arab Countries Approve Starlink LEO SATCOM Amid The Mounting Iranian Strike Munition Threat?

🇮🇷 🇸🇦 🇦🇪

The American company SpaceX offers satellite internet service in much of the world through its constellation of Starlink communication satellites. Although commercial satellite communications (SATCOM) is not new, Starlink is the first fully operational SATCOM service to utilize satellites that are located in low Earth orbit (LEO). While this forces SpaceX to place and maintain in orbit thousands of Starlink communication satellites, it results in a SATCOM service that is characterized by much lower latency and higher bandwidth than preceding geostationary Earth orbit (GEO) SATCOM services. Starlink and LEO SATCOM, more generally, therefore, offer a qualitatively superior SATCOM service to paying customers, a dynamic that has resulted in the unprecedentedly widespread usage of SATCOM by everyday persons worldwide.

To entice customers, Starlink offers fairly inexpensive antennas, which are required to communicate with one or more of the ever-expanding number of Starlink satellites in LEO, as well as fairly inexpensive subscription plans. While Starlink can be used to access the internet from remote locations—in jurisdictions that formally permit the American company to make use of the relevant parts of the electromagnetic spectrum on and above their territory—Starlink antennas can also be used as a SATCOM datalink to monitor, if not directly control, various types of military equipment, including both fixed-wing and multirotor drones. Starlink can also be used to help aircraft, whether crewed or uncrewed, navigate if and when global navigation satellite system (GNSS) signals, such as the American Global Positioning System (GPS), are inaccurate or unreliable. As a result, the advent of Starlink and other LEO SATCOM constellations more generally has profound implications for governments and militaries worldwide. Governments, including those of the Gulf Arab countries that are the focus of this post, have to decide whether the benefits of commercially available LEO SATCOM outweigh the inherent threat that these can pose when utilized by state and non-state adversaries alike.

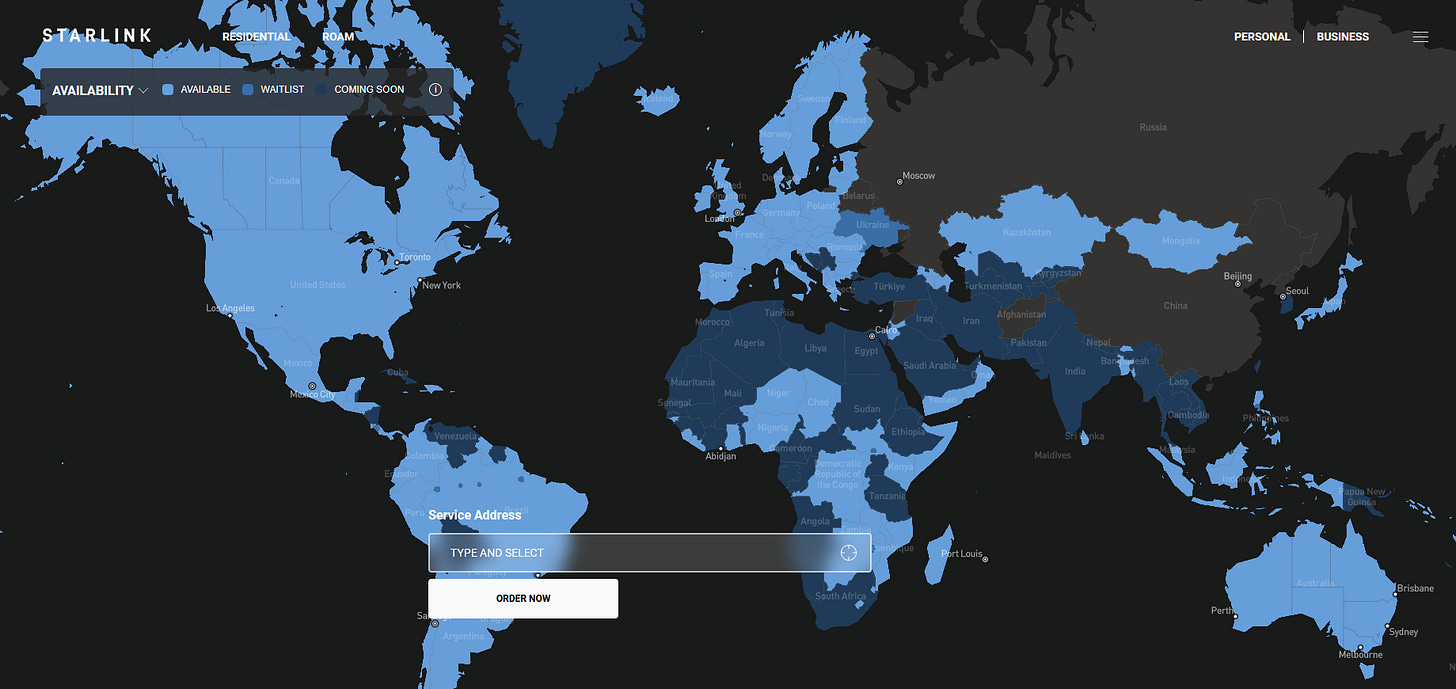

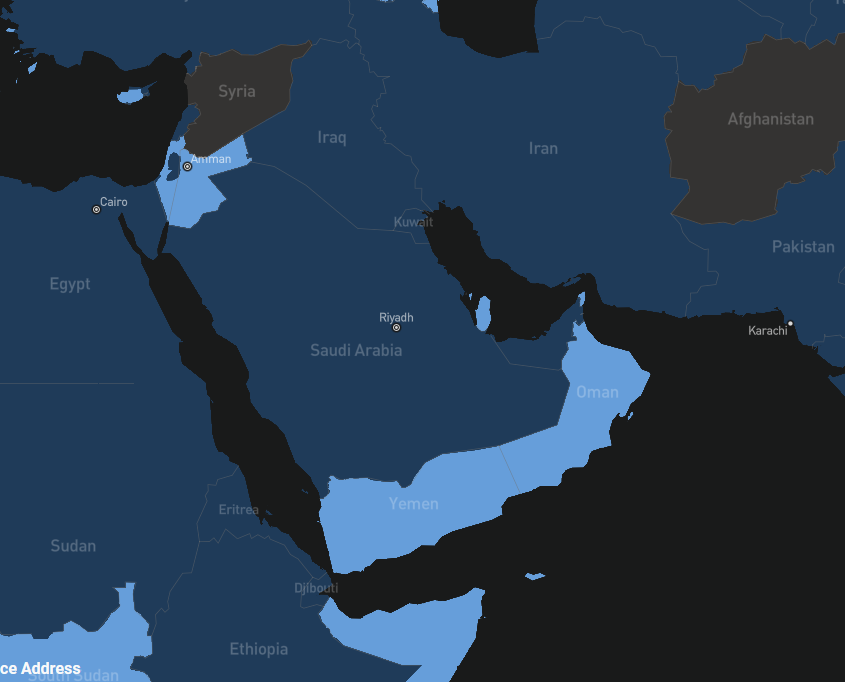

As the above maps indicate, Starlink’s LEO SATCOM service is not currently available in much of the Arabian Peninsula. All commercially-motivated LEO SATCOM providers face an inherent incentive to find as many paying customers as possible in every part of the world, given how the capacity to offer satellite internet over essentially the entire planet is an intrinsic attribute of any large satellite constellation in LEO—satellites in LEO do not remain stationary relative to a given position on the planet in the manner of GEO communications satellites. The Gulf Arab countries also amount to a potentially lucrative market for Starlink and other commercial LEO SATCOM providers, given how these are characterized by quite high disposable incomes, high internet utilization rates, and, in the case of the larger countries, a proclivity of a substantial part of populations to spend time outdoors in remote areas that are often beyond the coverage areas of mobile/cellular phone providers. Whatever the incentive structures that Starlink and other commercial LEO SATCOM providers encounter, the governments on Earth, not the companies that own the satellites in orbit, regulate the use of the electromagnetic spectrum on and above their territories under the regulatory frameworks of the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), which is a specialized agency of the United Nations. As a result, the above maps ultimately reflect the fact that Starlink has not yet received regulatory approval from the governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

While I am not privy to the deliberations among decision-makers in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, it is important to recognize that the relevant decision-makers are likely to be concerned about the inherent threat that Starlink and commercially available LEO SATCOM more generally will pose if and when it is employed by Iran and Iran’s non-state allies across the Middle East. Much as Ukraine has equipped both multirotor and fixed-wing drones, as well as uncrewed surface vehicles (USVs), among other military systems, with Starlink LEO SATCOM antennas for use against Russia, Iran and its non-state allies can readily make use of Starlink’s satellite internet service to greatly improve the accuracy of their strike munitions—when flying over countries in which Starlink is readily accessible—to target the Gulf Arab countries.

As things stand, Starlink and LEO SATCOM more generally hold the potential to greatly enhance the accuracy of Iranian strike munitions. The core components of Iran’s regional strike capabilities are the country’s ballistic missiles, its land-attack cruise missiles, and its propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drones. All three core components of Iran’s regional strike capabilities—especially the country’s propeller-driven strike drones, which likely constitute the bulk of its strike munition arsenal—are heavily reliant on the availability of accurate and reliable GNSS positioning data, which can be denied through GNSS jamming and/or spoofing using electronic warfare systems. Like other countries, Iran employs GNSS signals to augment the onboard inertial navigation system (INS)—which are built to different price points and, as such, different levels of sophistication and accuracy—given how INS systems are subject to drift—compounding inaccuracy—over time. This is a particular challenge when it comes to the employment of fairly slow propeller-driven fixed-wing strike drones like the Shahed-136, which is powered by a small 50-horsepower four-cylinder piston engine and has a cruise speed of just ~170 kilometers per hour while having a nominal maximum range of ~2000 kilometers. This results in a maximum flight time of around 12 hours and a lot of scope for inaccuracy when the INS is not corrected by accurate and reliable GNSS signals over the flight path.

Countries which encounter adversary strike munitions that are heavily reliant on the availability of accurate and reliable GNSS positioning data have an incentive to invest in electronic warfare systems that can be used to jam and/or spoof GNSS signals. Jamming and/or spoofing GNSS signals, however, tends to be highly indiscriminate and has increasingly profound fratricidal effects in a world in which so many consumer devices and pieces of industrial equipment and similar are reliant on the availability of accurate and reliable GNSS signals, which notably provide Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT). As a result, governments must decide when and where to jam and/or spoof GNSS signals. Facing a major threat from Iranian-supplied strike munitions in the arsenal of Hizballah in Lebanon and, to a lesser extent, Iranian-supplied strike munitions in the arsenals of Iran’s various Iraqi non-state allies as well as Ansarallah in Yemen, Israel decided to jam and spoof GNSS signals as part of its (ongoing) air defence efforts from October 2023 onward. As a consequence, Israeli civilians and the country’s economy more generally have been operating in a degraded GNSS environment. This has negatively affected the Israeli economy, given the everyday reliance of residents and companies on the availability of accurate and reliable GNSS positioning data for PNT, including fairly mundane tasks such as navigating roads and requesting a taxi. The fratricidal effects of Israeli electronic warfare efforts have notably extended to neighbouring countries, including Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt.

Despite the above dynamics, the Gulf Arab countries appear to be unwilling to readily undertake wide-area GNSS jamming and/or spoofing efforts, at least not short of an all-out conflict with Iran. The accuracy and reliability of GNSS signals appear to have been largely unaffected in the Gulf Arab countries during the June 2025 Iran-Israel War. This notably includes Qatar, which was the target of a one-off and very brief Iranian ballistic missile attack directed against American military forces garrisoned at al-Udeid airbase. Qatar appears to have decided that the costs of denying Iranian strike munitions accurate and reliable GNSS positioning data—the fratricidal effects on its inhabitants and economy—outweighed the benefits, at least given the threat posed by what is understood to have been a limited-scale Iranian ballistic missile attack for which advance notice was given.

When it comes to Starlink and LEO SATCOM more generally, the Gulf Arab countries encounter a broadly similar dynamic even as the stakes are in important respects much greater. LEO SATCOM is not merely a potential substitute for accurate and reliable GNSS positioning data; it can enable the employment of existing strike munitions in entirely new ways. Not jamming and/or spoofing GNSS signals will mean that an Iranian Shahed-136 propeller-driven strike drone will, for example, be able to accurately navigate a fairly complex pre-programmed flight path of some 1500 kilometers from Iran to Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coastline or a less complex flight path of some 400 kilometers from Iran toward the southern coast of the Persian Gulf. Enabling Starlink, however, will not only offer the Shahed-136 accurate and reliable positioning data while flying over the Gulf Arab countries but also allow Iranian military personnel to remotely monitor and, if required, directly control the Shahed-136 so as to attack a target of opportunity, attack moving/mobile targets including air defence systems, and more generally detect and avoid air defences. In other words, readily available LEO SATCOM is a much greater threat when integrated onto strike munitions than readily available PNT through GNSS could ever be.

As with all actively emitting radio frequency systems, Starlink and other LEO communication satellites more generally can, in principle, be jammed and spoofed. In practice, this is far more complicated than jamming and/or spoofing GNSS signals, not least as a result of the higher power signals being emitted by satellites located some 550 kilometers from the planet—in LEO—as opposed to over 20,000 kilometers from the planet. When it comes to Starlink and other LEO SATCOM systems more generally, governments that have good relations with both Starlink and its parent company SpaceX and, above all, the United States government, are likely to prefer something in the vein of a “kill switch” that allows governments to terminate availability of LEO SATCOM over their territory, at least to non-government users/receivers, when required. Such measures will, of course, have fratricidal effects on civilian life and the economy, especially as Starlink and other commercial satellite internet providers come to play an increasingly central role in a country’s telecommunications infrastructure. Without such a “kill switch,” the Gulf Arab countries are likely to face a significantly enhanced threat from Iranian strike munitions, including those operated by Iran’s various non-state allies across the Middle East.

While this post focuses on the Gulf Arab countries, it is important to recognize that the implications of Starlink and LEO SATCOM more generally are much the same worldwide. Countries that allow Starlink to offer satellite internet service to paying customers on and above their territory are assuming non-zero risk. For most countries, the risks are fairly small, given that the threat posed by strike munitions operated by state and/or non-state adversaries is also very small. The use of Starlink in the Russia-Ukraine War, including Ukraine’s use of Starlink to remotely operate USVs to target Russian warships at sea in the manner of a remotely piloted surface-running torpedo, should serve as a cautionary tale to decision-makers worldwide. Unlike cellular data services through which mobile phones connect to the internet, which can be readily disabled on demand, governments have very little control over the availability of LEO SATCOM internet services on and above their territory beyond the formalities of the ITU, and LEO SATCOM is also accessible in international airspace and international waters, which presents its own set of challenges.

PS: While Starlink’s satellite internet service is available in Bahrain and Qatar, it is important to recognize that these are not “transit countries” when it comes to Iran’s employment of strike munitions such as the Shahed-136, and Iran can readily target these countries with strike munitions that only fly over the Persian Gulf. These countries also lack the territorial depth of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. If Starlink and LEO SATCOM more generally become available across the Arabian Peninsula, then Iran can send the likes of the Shahed-136 on very circuitous routes to, for example, target Abu Dhabi (UAE) and the Dammam metropolitan area (Saudi Arabia) from the ~south, following lengthy transits over primarily unpopulated desert.